By Allison Sheridan and Scott M. Waring

Download PDF – Volume 1, Issue 1, Spring 2021, Article 4

Creating citizens who are active within their communities and government has long been a goal of education. Teachers, especially those who teach social studies, are tasked with finding ways to promote this within their curriculum. One way to demonstrate to students how they can be civically active is to include primary sources that promote civic engagement in the curriculum. The purpose of this article is to provide educators with a brief overview of civic engagement and an example, beyond traditional approaches, of how to incorporate primary sources to empower and engage students civically.

What is Civic Engagement

Civic engagement is a difficult concept to define (Hatcher, 2010). Some have used the term to describe how active one is within their community (Adler & Groggin, 2005), while others have portrayed it as the collective action of people to address issues of concern within their community (Checkoway & Aldana, 2013). The American Association of Colleges and Universities (2009) argued that authentic civic engagement is complex and includes knowledge, skills, values, and motivation of individuals. Additionally, this approach to authentic civic engagement should focus on “how to think, not what to think” and avoid an authoritarian approach to instruction (Fallace, 2020). Zaff et al. (2010) combine these thoughts and define civic engagement as the individual and collective actions that are intended to identify and address issues of the communities in which people live. Hollister (2002) prefers the term “active citizenship” over civic engagement and defines this idea as a collaboration of individuals in various platforms to pursue community issues. Others have tied civic engagement to solving issues through political participation (Diller, 2001). However one chooses to define civic engagement, all definitions seem to have one thing in common: people, either individually or collectively, participating within their communities and government in order to address issues of concern and to work towards enacting change.

For youth, civic engagement can come in many forms outside the traditional classroom environment, such as volunteering or involvement in organizations (clubs, sports teams, etc.). Civic engagement can also include activities within one’s community, such as serving food at a homeless shelter or writing a letter to a newspaper. Scholars have suggested that higher levels of youth participation in civically focused organized activities or groups have had direct positive impacts on their levels of civic engagement as an adult (Hanks, 1981; Kirlin, 2003).

The type of instruction a student receives in school can have an impact on their levels of civic engagement in their personal life, as well. According to the National Council for Social Studies (NCSS), a high-quality civically engaged educational program should grant young people the tools and methods for clear and disciplined thinking in order to navigate successfully in the worlds of college, career, and civic life (2013). The belief in using such strategies is that there will be an increase in civic engagement among young people (Manning & Edwards, 2014).

In 2003, the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) published The Civic Mission of Schools, which listed six approaches to teaching civics that would increase student civic engagement. One approach is that teachers incorporate discussions of current, local, national, and international issues and events in the classroom, particularly those topics that young people view as relevant to their lives. Incorporating primary sources, such as newspapers, editorial cartoons, editorials, and speeches, into lessons can offer students the ability to analyze multiple perspectives and discuss those issues to develop a connection and opinion regarding issues communities face today. In isolation, lecturing about rights and duties does not help students fully understand the concept of civic engagement.

To combat the “stand and deliver” instructional method, introducing or including tangible primary sources, such as a letter to congress or a petition to local government officials, can help students visualize how others in the past have engaged civically (Potter, 2005) and, therefore, begin to understand how they can do the same. Through the use of primary sources, educators can bring voices of the past to life, clarify and amplify concepts being learned, and fuel a student’s curiosity and engagement about events that happened well before their time, as well as those in the present day (Hunt, 1998). Teaching with sources that showcase voices from children, such as letters, petitions, and photographs, sends the message that students that children can serve as agents of change and do not have to wait until they are 18 to be a participant in various civic arenas (Munn & Wickens, 2018). This is not to say teachers should just hand students primary sources and expect them to know what to do. Teachers will have to implement and guide students through an investigative process, employ a particular chosen framework for inquiry, such as the SOURCES Framework for Teaching with Primary and Secondary Sources (Waring, 2020), and scaffold the learning process until students are comfortable enough to conduct learning on a more independent level. Through the integration of primary sources, teachers can also lead the class in discussions of topics of interest, relevance, and importance to them and their lives. The point is that teachers are not telling students the information but, rather, leading students along a pathway to discover information through other sources than the textbook.

Primary sources offer students information beyond what is presented in their textbooks and provide perspectives that may not be included within the text being read or through classroom lectures. Examining primary sources allows students to construct their own narratives as they compare and critically analyze various perspectives and information with which they are presented (Fitzgerald, 2009). Additionally, primary sources can introduce authors or perspectives that students may be better able to connect with, outside of the traditional narrative presented in textbooks. In order to increase a student’s ability to think critically and civically, it is imperative that they examine multiple perspectives, in the form of primary sources, to be able to come to clearer historical understandings and, in turn, have opportunities to construct their own unique narratives (Barton, 2005).

Bolstering the Use of Foundational Primary Sources in the Classroom

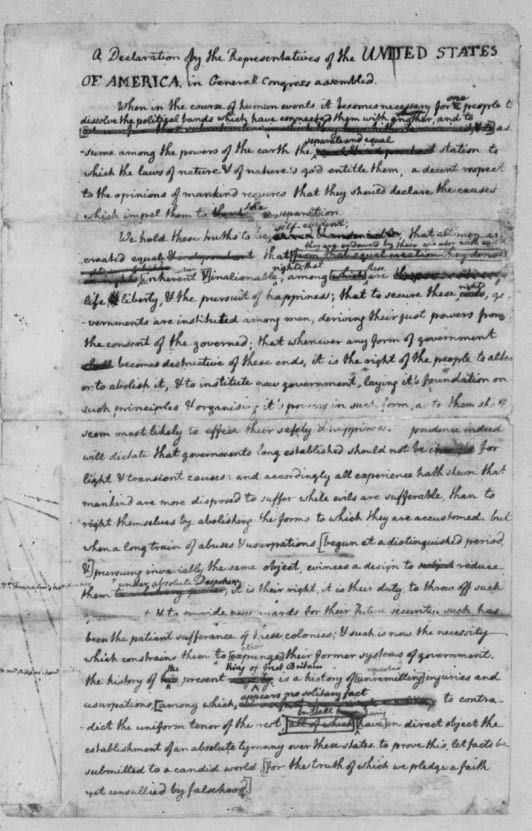

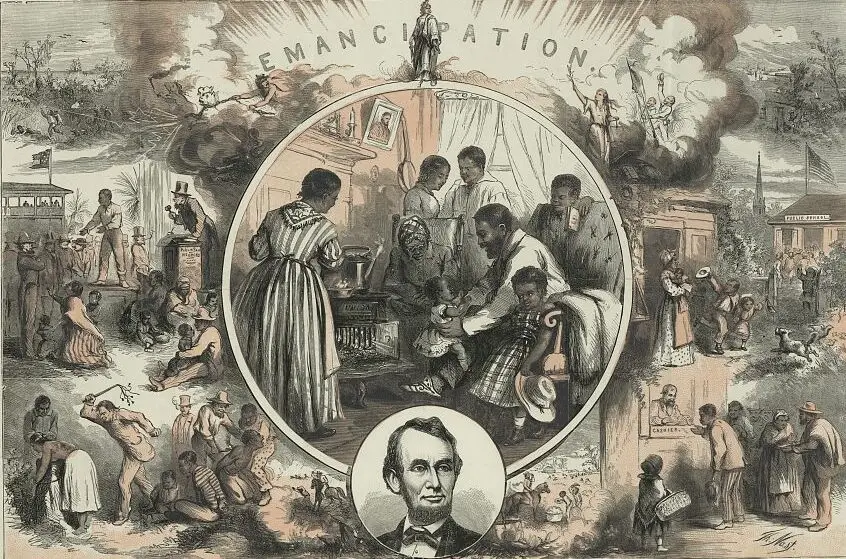

Our nation’s founding documents, such as the Declaration of Independence or the Constitution, are often the go-to sources for implementing the use of primary sources in the American history and government classrooms. We agree that these are important to include but would advocate for the use of additional sources to complement our founding documents and make examining these sources more engaging. For example, Thomas Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration of Independence (Figure 1) can offer students a view of how much debate and change went into creating this document.

Figure 1. Thomas Jefferson’s Draft of the Declaration of Independence

The most notable section left out of the final version occurs on page 3 of Jefferson’s draft and addresses slavery. Students can infer why this part was left out, based on their prior knowledge of what was happening in the colonies during those times and how they think Thomas Jefferson felt once those changes were made to what he initially wrote.

Teachers can offer students a glimpse into the changes that George Washington made to the original draft of the Constitution. Examining Washington’s notes, with proper scaffolding, can lead them to question whether these changes were necessary or even beneficial. Introducing the lyrics for the Star-Spangled Banner might inspire students to discuss how or why these lyrics have led to protests within the past few years.

While the founding documents are important for students to examine, using less common primary sources or topics potentially extends their understanding of civic engagement and agency. In addition to this, students need to have opportunities to see and examine sources relevant to them and to be provided with examples and topics to which they can relate.

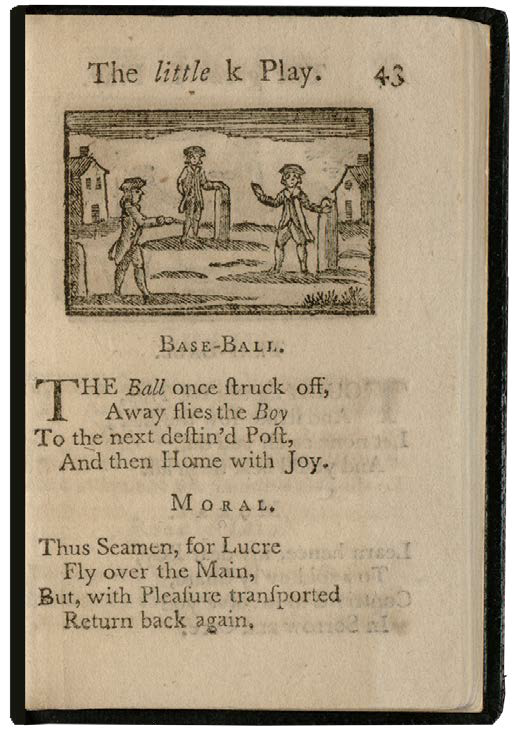

Figure 2. A Little Pretty Pocket Book

Using Baseball Related Primary Sources to Build Capacity for Agency

Teachers can introduce unexpected primary sources to increase a student’s civic mindedness and engagement, allow them to appreciate their own agentic powers, and lead them to move beyond thinking and toward enacting change. Since many students have an interest in sports, one way to demonstrate the capacity for individuals and groups to impact their community and serve as change agents is through the investigation of America’s pastime of baseball. To pique interest, students can begin by looking at the poem “Base-Ball”. This poem is found in the book, A Little Pretty Pocket Book, first published in England in 1744 about outdoor activities suitable to “instruct and amuse” children. The first American edition was published in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1787. Although legend has it that Abner Doubleday invented the sport in 1839, this source, as well as many others, help to debunk that myth (Figure 2).

By investigating various sources, students can discover the evolution of the name of the game itself from Base-Ball (1787), to base-ball (1799), to base ball (1818), to Base Ball (1845), and eventually to baseball (1899).

Once students have had a chance to think about the game of baseball, a teacher can inquire as to how a sport, such as baseball, may be used as a tool for civic engagement. In a source from 1916 (Figure 3), “Girls organize sure ‘nough ball club – know how to play”, students can learn about how Ida Schnall felt the need for the creation of a female baseball team in Los Angeles. This was evident to her especially after seeing the success of the New York Female Giants. This led Schnall to determine that she needed to make an effort to replicate what she had seen in New York in the western portion of the United States. The information that this team was constructed when women did not even have the right to vote may help students gain a better understanding of the historical context. Many may have been discouraged when thinking about the prospect of creating an all-women’s baseball team. Students may consider how efforts like this one helped lead to the 19th Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which was passed by Congress just a short time after this on June 4, 1919. This newspaper article indicates that more than twenty players showed up for the first tryout and the numbers increased daily. This was considered to be a testament to the interest for a team and is what ultimately ended up being a good problem to have, as Schnall’s “greatest difficulty now seems to be the final choice of first team players.” Students can conclude that there was an apparent interest in having a female team in the Los Angeles area, and thanks to Schnall this became a reality. It was a very different time and society norms and standards were quite different than today. To extend their thinking, teachers might engage students in an economic discussion with the information that in 1916, a dozen eggs cost 38 cents, a gallon of milk delivered to one’s home cost 36 cents, and a pound of coffee cost 30 cents (United States Department of Commerce, 1975).

Figure 3. “Girls organize sure ‘nough ball club – know how to play”

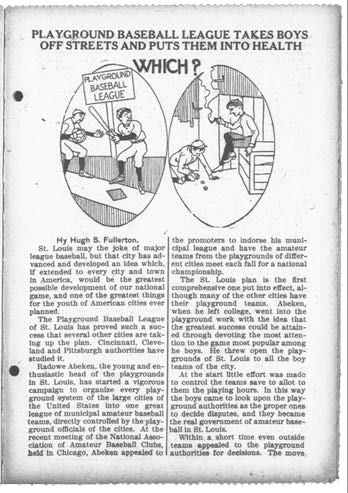

Around the same time, there were concerted efforts to improve the conditions of America’s youth, such as greater focus and effort to find solutions for various health-related issues and conditions, increased educational opportunities, and legislating limitations on child labor practices. With this in mind, students can examine and discuss a source published in 1914 (Figure 4), titled “Playground baseball league takes boys off streets and puts them into health.” Here, students learn that Radowe Abeken, “the young and enthusiastic head of the playgrounds in St. Louis has started a vigorous campaign to organize every playground system of the large cities of the United States into one great league of municipal amateur baseball teams” so that collectively, communities may be able to “keep many boys away from the street corner gangs.”

Figure 4. Playground Baseball League Takes Boys Off Streets and Puts Them Into Health

Examining this source can provide a great opportunity to discuss ways in which individuals have utilized sports to improve conditions and lives throughout history and then transition into how this is being done today through the creation of leagues and teams for broader inclusion, efforts to eradicate racism from sports, make sports safer for the participants, and other similar efforts. This can lead students to think critically about how they might possibly use sports to help others in their own communities.

Students also can have conversations about how baseball was used during wartime. In this image of Union Prisoners at Salisbury, N.C. (Figure 5), students can see how the American Civil War added to the popularity of baseball. Union officers often encouraged off-duty soldiers to play in order to increase morale and foster camaraderie. Additionally, Union prisoners held in Confederate camps taught southerners, who were not familiar with the sport, about the rules of baseball and played games within the camps (Library of Congress, 2018).

Figure 5. Union Prisoners at Salisbury, N.C.

As baseball gained in popularity throughout the country in the second half of the 19th century, Japanese-Americans, mainly living on the west coast, began to see baseball as “a critical force in shaping identity, binding ethnic enclaves, forging ties within Japanese culture and promoting civil rights” (Maloney, 2018, para. 2). Since baseball leagues in the United States were not yet integrated, both African-Americans and Japanese-Americans were prohibited from playing in pre-existing organized leagues, so in some areas, they created their own leagues. The first team fielding Japanese-Americans arose in San Francisco in 1903 with the creation of the Fuji Athletic Club. As leagues and teams consisting of Japanese-Americans continued to develop and evolve, first-generation immigrants, as well as those born in the United States, began to see baseball as a modern equivalent to Kendo or Judo, with many seeing it as a sport that illustrated their dedication to American ideals and an opportunity to keep children away from “boozing, drugging or gambling their lives away in American environs” (Maloney, 2018, para. 9).

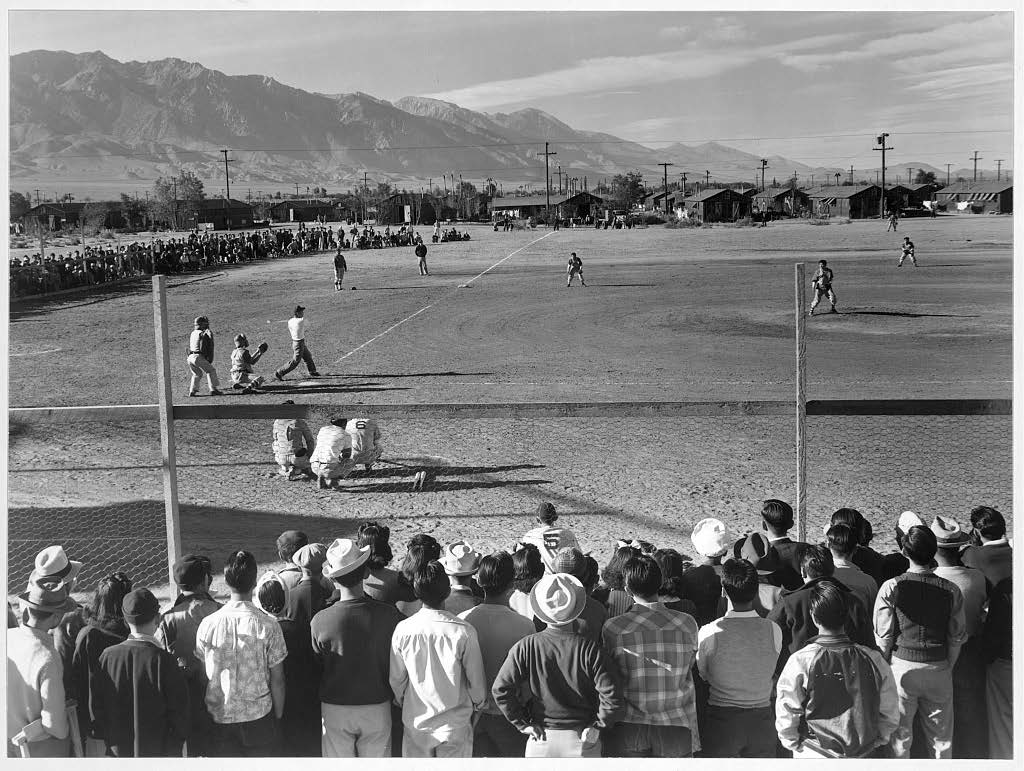

After the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the internment of those of Japanese ancestry, baseball was an opportunity to try to preserve some semblance of a normal life and provide a distraction to the life within the camps. In a photograph included in the Manzanar Free Press newspaper (Manzanar, California), from July 27, 1942, (Figure 6) students can see baseball being played at the camp with a caption that reads “Baseball…Manzanar’s favorite sport. One of 180 teams in action.” (https://www.loc.gov/item/sn84025948/1942-07-27/ed-1)

This is just one example of many of Japanese-American internees using baseball to raise dipping morale in Japanese internment camps. To take this investigation a step further, a teacher can read Baseball Saved Us, by Ken Mochizuki, and use various sources found on the Library of Congress website, as well as those within the Japanese Internment Camp primary source set (https://www.loc.gov/classroom-materials/japanese-american-internment).

To further the conversation, teachers can provide more contemporary examples of children becoming civically engaged through various types of sports. Instances of current youth involvement and activism, such as efforts for heads-up tackling in football, erasing racism in soccer, football, auto racing, and other sports, and creating community teams and leagues can be discussed in the classroom. This may lead to opportunities for the students to become more actively involved in sports or other youth programs in their communities and to gain a better appreciation for an athlete’s ability to enact change.

Figure 6. Photograph by Ansel Adams from 1943 entitled “Baseball game, Manzanar Relocation Center, Calif.”

Conclusion

Many educators have contemplated how best to define civic engagement and what activities increases a student’s willingness to participate as a citizen. Primary sources reflect events and experiences that occurred throughout our nation’s history and offer students a perspective often not found in textbooks of how ordinary citizens demonstrated civic behavior. When teachers incorporate primary source materials in the classroom, students learn to examine multiple perspectives to enrich their critical thinking and problem-solving skills. Rather than telling students what they can do, showing them what others have done to bring about change will empower them and encourage civic engagement, whether individually or through community collaborations. Using primary sources when teaching civic ideals and instilling civic mindedness does not always have to exclusively involve various founding documents, as teachers can find a variety of primary sources related to the interests of their students (sports, music, arts, etc.) to effectively accomplish this. Giving students the skills and ability to interact with and analyze sources will help them to more effectively examine and question sources they encounter on a daily basis. The ultimate goal of examining sources in this manner is to help students realize and believe that citizenship is not a spectator sport and that, without action, there is no change.

Authors

Allison Sheridan, Ph.D., teaches 7th grade civics and 8th grade U.S. history at Heritage Middle School, in Deland, Florida. She is a graduate of the Social Science Education program at the University of Central Florida.

Scott M. Waring, Ph.D., is a professor and program coordinator of the Social Science Education Program at the University of Central Florida. He serves as the editor of Social Studies and the Young Learner, the interdisciplinary feature editor of Social Studies Research and Practice, and the editor of the TPS Consortium Journal. The University of Central Florida has been a member of the TPS Consortium since 2010.

References

Adler, R. P., & Goggin, J. (2005). What do we mean by “Civic Engagement”? Journal of Transformative Education, 3(3), 236-253.

American Association of Colleges and Universities. (2009). VALUE rubrics: Valid assessment of learning in undergraduate education. https://www.aacu.org/value/metarubrics.cfm

Barton, K. C. (2005). Primary sources in history: Breaking through the myths. The Phi Delta Kappan, 86(10), 745-753.

Carnegie Corporation of New York and the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement. (2003). The civic mission of schools. https://media.carnegie.org/filer_public/9d/0a/9d0af9f4-06af-4cc6-ae7d-71a2ae2b93d7/ccny_report_2003_civicmission.pdf

Checkoway, B., & Aldana, A. (2013). Four forms of youth civic engagement for diverse democracy. Children and Youth Services Review, 35, 1894-1899.

Cowgill, D., & Waring, S. M. (2015). Using SOURCES to examine the American Constitution and events leading to its construction. The Councilor: A Journal of the Social Studies, 76(2), 1–14.

Diller, E. C. (2001). Citizens in service: The challenge of delivering civic engagement training to national service programs. Corporation for National and Community Service.

Fallace, T. D. (2020). Schools and the specter of authoritarianism: How foreign threats shaped American education. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2020-10-14/schools-and-specter-authoritarianism

Fitzgerald, J. C. (2009). Textbooks and primary source analysis. Social Studies Research & Practice, 4(3), 37–45.

Hanks, M. (1981). Youth, voluntary associations, and political socialization. Social Forces, 60(1), 211-223.

Herlihy, C., & Waring, S. M. (2015). Using the SOURCES framework to examine the Little Rock Nine. Oregon Journal of the Social Studies, 3(2), 44–51.

Hollister, R. (2002, February 7). Lives of active citizenship. Inaugural talk, John DiBiaggio Chair in Citizenship and Public Service. Tufts University, Medford, MA.

Hunt, R. (1998). Using the records of Congress in the classroom. OAH Magazine of History, 12(4), 34-38.

Kirlin, M. (2002). Civic skill building: The missing component in service programs? Political Science and Politics, 35(3), 571-575.

LaVallee, C., Purdin, T., & Waring, S. M. (2019). Civil liberties, the Bill of Rights, and SOURCES: Engaging students in the past in order to prepare citizens of the future. In J. Hubbard (Ed.), Extending the ground of public confidence: Teaching civil liberties in K–16 social studies education (pp. 3–32). Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing.

LaVallee, C., & Waring, S. M. (2015). Using SOURCES to examine the Nadir of Race Relations (1890-1920). The Clearing House, 88, 133–139.

Library of Congress (2018). Baseball Americana: Civil War prisoners at play. https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/baseball-americana/about-this-exhibition/origins-and-early-days/baseball-as-the-national-game/civil-war-prisoners-at-play

Maloney, W. (2018, May 25). Japanese-America’s pastime: Baseball. Library of Congress blog. https://blogs.loc.gov/loc/2018/05/japanese-americas-pastime-baseball

Manning, N., & Edwards, K. (2014). Does civic education for young people increase political participation? A systematic review. Educational Review, 66 (1), 22-45.

Munn, K., & Wickens, K. A. (2018). Public history institutions: Leaders in civics through the power of the past. Journal of Museum Education, 43 (2), 91–103.

National Council for the Social Studies. (2013). The college, career, and civic life (C3) framework for social studies state standards: Guidance for enhancing the rigor of K–12 civics, economics, geography, and history. NCSS.

Potter, L. A. (2005). Teaching civics with primary source documents. Social Education, 69 (7), 358-359.

Terry, K., & Waring, S. M. (2017). Expanding historical narratives: Using SOURCES to assess the successes and failures of Operation Anthropoid. Social Studies Journal, 37 (2), 59–71.

United States Department of Commerce. (1975). Historical statistics of the United States, colonial times to 1970: Part 1. Bureau of the Census. https://www.google.com/books/edition/_/4uP8TZgLplgC?hl=en&gbpv=0

Waring, S. M. (2020). Integrating primary and secondary sources into teaching: The SOURCES Framework for Authentic Investigation. Teachers College Press.

Waring, S. M. (2017). Engaging history students through the use of the SOURCES Framework. In Context, 1 (1), 2–4.

Waring, S. M., & Hartshorne, R. (2020). Conducting authentic historical inquiry: Engaging learners with SOURCES and emerging technologies. Teachers College Press.

Waring, S. M., & Herlihy, C. (2015). Are we alone in the universe? Using primary sources to address a fundamental question. The Science Teacher, 82 (7), 63–66.

Waring, S. M., LaVallee, C., & Purdin, T. (2018). The power of agentic women and SOURCES. Social Studies Research and Practice, 13 (2), 270–278.

Waring, S. M., & Scheiner-Fisher, C. (2014). Using SOURCES to allow digital natives to explore the Lewis and Clark expedition. Middle School Journal, 45 (4), 3–12.

Waring, S. M., & Tapia-Moreno, D. (2015). Examining the conditions of Andersonville Prison through the use of SOURCES. The Social Studies, 106(4), 170–177.

Zaff, J., Boyd, M., Li, Y., Lerner, J., & Lerner, R. (2010). Active and engaged citizenship: Multi group and longitudinal factorial analysis of an integrated construct of civic engagement. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(7), 736–750.

![[Demonstrators marching in the street holding signs during the March on Washington, 1963] / MST.](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-ds-04000-04000v.webp)