By Jenna Spiering, Ph.D. and Daniella Ann Cook, Ph.D. (University of South Carolina)

Download PDF – Spring 2024, Article 4

The professional development model for the Teaching with Primary Sources Civil Rights Fellowship (TPS CRF) was unique in several ways as it: (a) encouraged collaboration between teaching partners, (b) encouraged their learning across several sites, and (c) took place over a significant period of time with several check-ins and products completed during that time. The design allowed for sustained inquiry as the TPS CRF Fellows met over the course of two years connecting their contextualized, place-based learning with multiple opportunities for peer-to-peer interaction. This led to more nuanced discussions and understandings of the civil rights movement (CRM).

In the final meeting of the TPS CRF, participating Fellows and Consortium members met to synthesize our learning and reflect on the overall experience. The Fellows reported that several aspects of the design were impactful for a variety of reasons including: (a) the importance of access to the Library of Congress’s resources, (b) the significance of the Fellowship community for nurturing confidence in teaching the movement, and (3) the space and time that was afforded and necessary to “push” educators to create new material and lessons. Their responses illustrated the specific benefits of the program, as well as important directions forward for future professional development sessions employing this model. In this piece, we share illustrative comments from participants in the culminating conversation.

Access to Resources and Community

An explicit goal of the TPS CRF was to shed light on all that is available for educators within the Library of Congress’s vast resources. Many participants in our program expressed their personal connections to individual items in the collection. However, participants navigating the vast resources of the Library has been a perennial challenge. Creating sustained opportunities to engage the collection within a disciplinary community of practice addresses this concern. For the Fellows, space and time to engage with these resources allowed them to imagine how they would be used in classrooms. One participant shared:

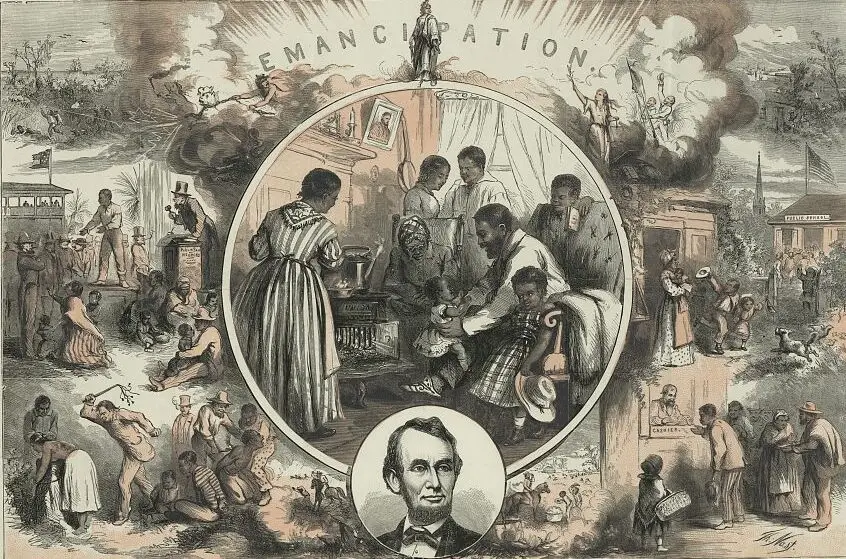

It just blew my mind how many resources and how many collections were available that I never knew existed…I will have to say, my favorite over the last two years is when I got my hands on Rosa Parks’s papers (Rosa Parks: In Her Own Words). To read her version of that day, because you hear so many different versions of what happened that day. She was tired. There’s this and that, you know, and she plainly says, “I wasn’t tired. Let me tell you why”. And so they hear it from her.

Many participants highlighted the benefits of being in a community of educators working together to deepen their own teaching and learning. This was a core component of the Fellowship’s design.

In order to “stay in the difficult conversations” (Oliver, 2016, p. 32) and engage with the complexities of the movement, educators need to be in conversation with one another and the primary source materials. Time was required to not only build trust but cultivate a common understanding and language about race and racism. The Fellowship made time for and incentivized this effort. This was important for white and BIPOC (Black, indigenous, and other people of Color) educators. One participant shared the following:

In order to “stay in the difficult conversations” (Oliver, 2016, p. 32) and engage with the complexities of the movement, educators need to be in conversation with one another and the primary source materials. Time was required to not only build trust but cultivate a common understanding and language about race and racism. The Fellowship made time for and incentivized this effort. This was important for white and BIPOC (Black, indigenous, and other people of Color) educators. One participant shared the following:

When I first started teaching the African American History course, you know, I had to develop the course myself. And then later, after struggling, I joined this group. And bam, there’s already prepared lesson plans for African American history teachers on the teacher site (referring to classroom materials available from the Library’s Teachers site), and just having those resources available really changes how (emphasis ours) we teach and what we teach. And we’re not just coming from our own vantage point, but some other experienced teachers that put those resources together. Now I feel like I’m part of a community (emphasis ours), and I don’t have to go it alone.

Clearly, community matters. Over the course of two years, time was intentionally created in support of educators accessing the Library’s resources. In addition, professional development sessions created space to share strategies for selecting sources that prompted students to engage with and stay in difficult conversations.

Confidence Teaching the Civil Rights Movement with Students

Many participants agreed that a fundamental benefit of the program was increased confidence in teaching the movement with more nuance. While gaining a deeper understanding of the content, one participant shared that he thought about how (emphasis ours) students would receive the content coming from him as a white person:

Some subjects you wonder how the students will perceive or if they will judge you for trying to teach it in a certain way. And so, I think I have a little bit more of a comfort level that allows me to open up a little bit more.

For this educator, participation in the TPS CRF increased his confidence in teaching the long arc of the CRM and with the local connections that make the content impactful for his students. This could be one potential reason why so many educators rely on traditional and familiar narratives about the CRM in their classrooms rather than engaging with more complex histories. While we often expect that content area teachers are masters of their subjects, professional development that creates space for continued content learning is important.

Inspiration for the Classroom and a “Push” to Create New Material

Deep engagement with the primary sources available through the Library of Congress cannot always be achieved during a typical educator’s workday. This is not due to complacency but rather the very real time constraints of the school day that inhibit re-envisioning the curriculum. One meaningful way of changing how the CRM is taught is achieved simply when we give educators time to work in a community of shared interests and commitments. Without a supportive community, it is easier to continue teaching the dominant narrative. One participant shared in their final reflection about the TPS CRF:

The other thing is the push to [create the] lesson plans [referring to required products]. And sometimes in the moment, it was a little hard. And I’m like Oh, I’ve got some of the other things on my list. But it [the TPS CRF] always pushed me to make something better and cooler. And the kids always liked the lesson plans. And I’ve been doing the one that I created in our slavery section, every semester since, and the kids have really liked it and gotten into it. And so sometimes you need that push, and like that inspiration… So, if [I] make a cool lesson…or find the new resources in it, and then it gives me inspiration in the classroom. Like, yes, this is going right, and I can make this work and it re-energizes me. But sometimes I need that push to make the new lesson, right? To get out there and see what’s there. Because there are so many other things on that to-do list we have as a teacher. So, I’ve really liked what I’ve created and what I’ve seen some of the other people create. And I like that I’m able to use them now and have that energy going into a new semester to create new things.

The TPS CRF nurtured space for educators to grow in their practice within a community and made an impact not only on individual educators but more importantly their students.

Conclusion

Students are energized, more eager than ever to learn all there is to know about America’s past, in order to understand the complexities of America’s present, so they can adequately address the challenges to come in America’s future. And they are [like their educators] looking to the civil rights movement as they search for a blueprint for how to end axial prejudice and stamp out racial inequality. (Jeffries, 2019, p. xiv)

From participants’ comments at the culminating meeting, several themes emerged including the importance of creating space, time, and community for educators to engage with high-quality resources, build their own content knowledge, and craft meaningful lessons. The professional development model employed in this project allowed for sustained inquiry into the long arc of the CRM – one that not only engaged participants with primary sources but with powerful local and personal connections, as well.

References

Jeffries, H. K. (Ed.). (2019). Understanding and teaching the civil rights movement. University of Wisconsin Press.

Oliver, S. T. (2016). Dealing with things as they are: Creating a classroom environment for teaching slavery and its lingering impact. In B. Jay & C. L. Lyerly (Eds.), Understanding and teaching American slavery (pp. 31-42). University of Wisconsin Press.

![[African American men, women and children outside of church]](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-cph-3c00000-3c03000-3c03300-3c03393v-e1708980496747.webp)