By Kara Knight

Download PDF – Volume 1, Issue 1, Spring 2021, Article 2

Seated on the floor facing their teacher, a group of third graders listen intently to a question posed by their classmate: “Does segregation still exist today?” she asks. “Because if it does, where … and why?”

One week prior, these third-grade students in a Saint Paul, Minnesota suburb did not understand the long history of racial segregation in the United States. Using historical inquiry with primary sources, teacher Kellie Friend of Turtle Lake Elementary School (Mounds View Public Schools) introduced a lesson examining segregation past and present during the 2017-18 school year (Culturally Relevant Pedagogy with Primary Sources Video: Tenet 3, 2018). Structuring her lesson plan over three days, Friend carefully scaffolded her students’ knowledge of school segregation history, their historical analysis and inquiry skills, and their understanding.

By showing her third graders how students in the past were impacted by segregation and how they took action to change it, Friend empowered her students to think critically about the past, critique how much life has changed today, and see themselves and other young people like them as agents of change. This article demonstrates how two powerful instructional frameworks — culturally relevant pedagogy and historical inquiry using primary sources — can support understanding and development of civic ideals and practices at the elementary level (NCSS, p. 62-65).

“Somehow we found the power, didn’t we?” Friend replied fervently. “People found the power. You are the people. You are the citizens of this country and you can change it.”

Part of Who We Are is Where We Came From

In 1992, Dr. Gloria Ladson-Billings coined the term “culturally relevant pedagogy,” which refers to the pedagogical practices, lenses, and mindsets associated with creating a safe and inclusive classroom where all students — no matter their cultural background — can participate in meaningful and engaging learning. According to Ladson-Billings, a culturally relevant classroom is a place where students experience academic success, develop their cultural competence, and examine and critique the status quo (1995, p. 160). In 2014, Ladson-Billings described the three tenets in this way:

By academic success I refer to the intellectual growth that students experience as a result of classroom instruction and learning experiences. Cultural competence refers to the ability to help students appreciate and celebrate their cultures of origin while gaining knowledge of and fluency in at least one other culture. Sociopolitical consciousness [critiquing the status quo] is the ability to take learning beyond the confines of the classroom using school knowledge and skills to identify, analyze, and solve real-world problems. (p. 75)

These three tenets provide a lens through which to view not only pedagogical choices, but also curriculum choices, school structures, and community engagement. As her research findings became increasingly put into practice, Ladson-Billings observed that many teachers attempting to implement culturally relevant pedagogy “rarely pushed students to consider critical perspectives on policies and practices that may have direct impact on their lives and communities” (Ladson-Billings, 2014, p. 78). Digging into relevant and important issues of the day can be daunting, uncomfortable, and sometimes emotional with students of any age. In the classroom example highlighted in this article, third-grade teacher Kellie Friend shows how examining and critiquing the status quo is achievable with elementary learners and how historical inquiry with primary sources can help scaffold students to do that work.

One of the main principles of the social studies is to “emphasize skills and practices as preparation for democratic decision-making” (NCSS, 2013). To that end, the inquiry process, as outlined in the C3 framework (2013, p. 17), provides a structure through which students interpret information for themselves and acquire the higher order thinking skills necessary for democratic civic engagement (Lewis, 2019). This framework offers a fundamental shift from traditional instruction, where factual information is memorized and assessed for retention.

Since the social studies writ large encompass the study of society — in its very essence, the stories of us — the process of constructing knowledge within these disciplines can sometimes feel controversial. The inquiry process can result in students developing conclusions or interpretations that are at odds with each other or with those of their teachers, parents, or community members. Django Paris, author of Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies, points out that traditional instruction, and the educational policies that reinforce it, not only deemphasizes higher order thinking skills, but also “has quite the explicit goal of creating a monocultural and monolingual society based on White, middle-class norms of language and cultural being” (2012, p. 95).

Though inquiry and culturally relevant pedagogy are by no means new instructional concepts, it can be a challenge for some educators to implement them as central instructional tools when surrounded by educational policies and initiatives that implicitly (or explicitly) discourage those pedagogical practices, such as prioritizing time to prepare for standardized tests at the expense of co-constructing skills and knowledge with students. If, however, “schools are to prepare students for active citizenship in a democracy, they can neither ignore controversy nor teach students to passively accept someone else’s historical interpretations” (Levstik & Barton, 2011, p. 10). Using inquiry as the structure, cultural relevance as the lens, and historical primary source images as the content, third-grade teacher Kellie Friend created an opportunity for her students to question what is considered normal or the status quo and formulate new ways of thinking about how people organize themselves within society today.

Using primary source evidence to study how children in the past affected change can help students “see themselves and others as having historical agency—the power to make history” (Levstik & Barton, 2011, p. 113). In Friend’s lesson, students were introduced to images and stories of young children their own age who were impacted by segregation, took a stand against it, and integrated schools. By studying these children of the past, Friend’s students began to see opportunities for further change, and consider civic action they could take, as well.

“I think we can change even more,” one student offered quietly.

“In what way?” Friend inquired.

“Like, there probably still is … might be a little bit of segregation and they might be in other countries. So we could help with that.”

“Absolutely,” said Friend. “How would we help them out?”

“Well, we could kind of go over there. Well, it would be kind of far. If there was any kind of fight, you don’t have to go there just to kind of protest.”

Primary sources provide uninterpreted artifacts that can disrupt and complicate the traditional interpretation of American history often found in many secondary sources designed for students, like textbooks. On this topic, Levstik and Barton (2011) wrote:

Because issues of race, gender, and class still divide our society, every attempt to tell a more inclusive story of U.S. history is met with fierce resistance, as defenders of the status quo argue that these attempts minimize the achievements of the men who made our country great. (p. 8)

Primary sources can help students ground themselves in a historical time period without the influence of modern interpretations, biases, or of those who stand to gain by reinforcing the status quo. Students should be given the opportunity to draw their own conclusions about what primary sources reveal, the perspectives they preserve, and how that applies to what it means to be an American, past and present. While students, especially those at the elementary level, often have misconceptions (of course they do – they’re learning this stuff for the first time!), it is important to teach them how to grapple with complexity and how to not only draw conclusions, but revise them when more information proves their initial conclusion inadequate or incorrect. These are skills needed by an informed citizenry in the 21st century. When educators maintain authority as the gate-keepers of knowledge, we rob our students of the skills and processes they need to be discerning and thoughtful consumers of information.

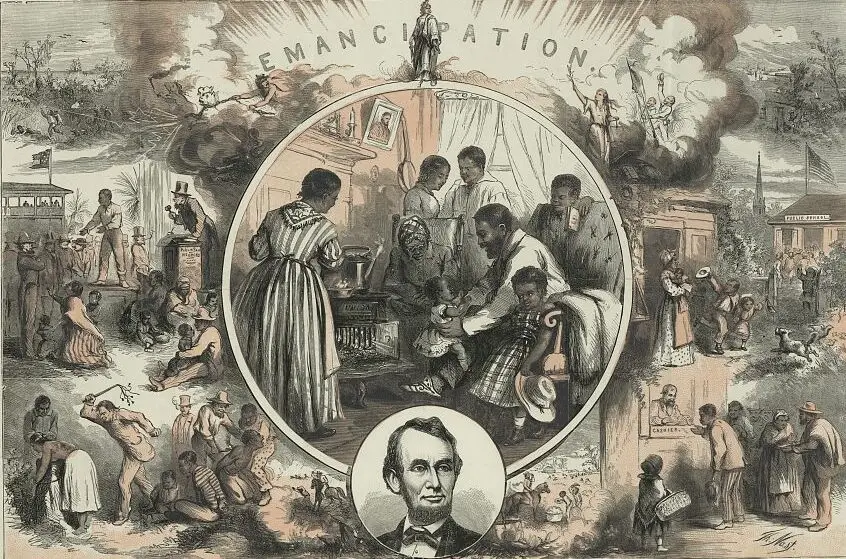

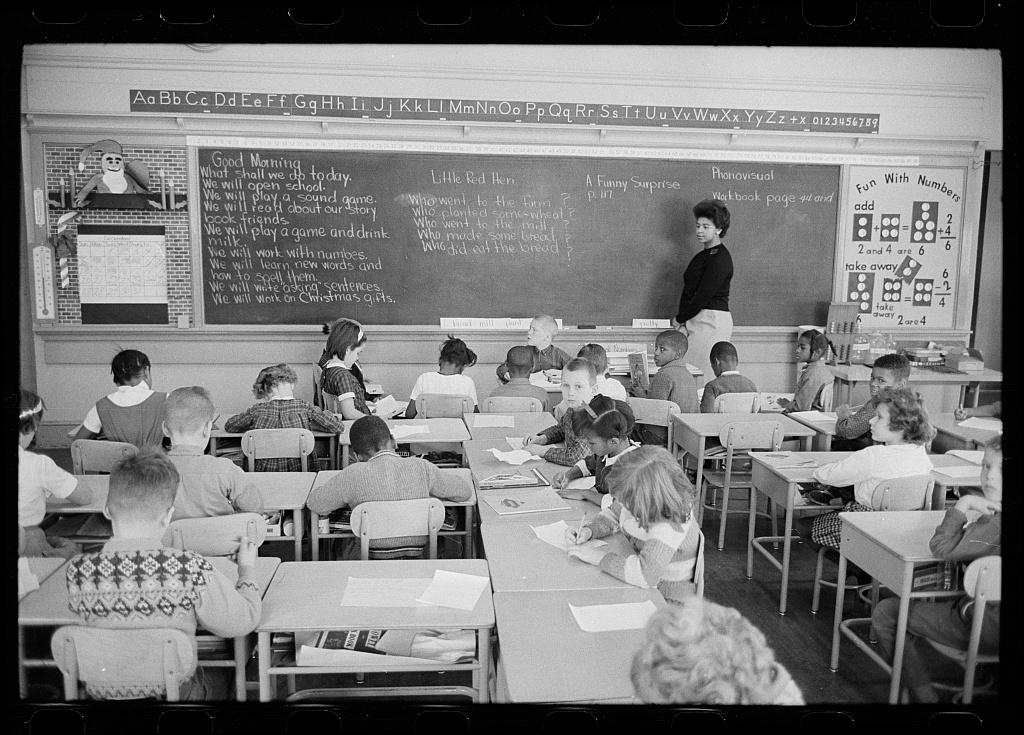

Figure 1. Kellie Friend’s Third-Grade Classroom in Turtle Lake Elementary School

Examining Segregation with Third Graders

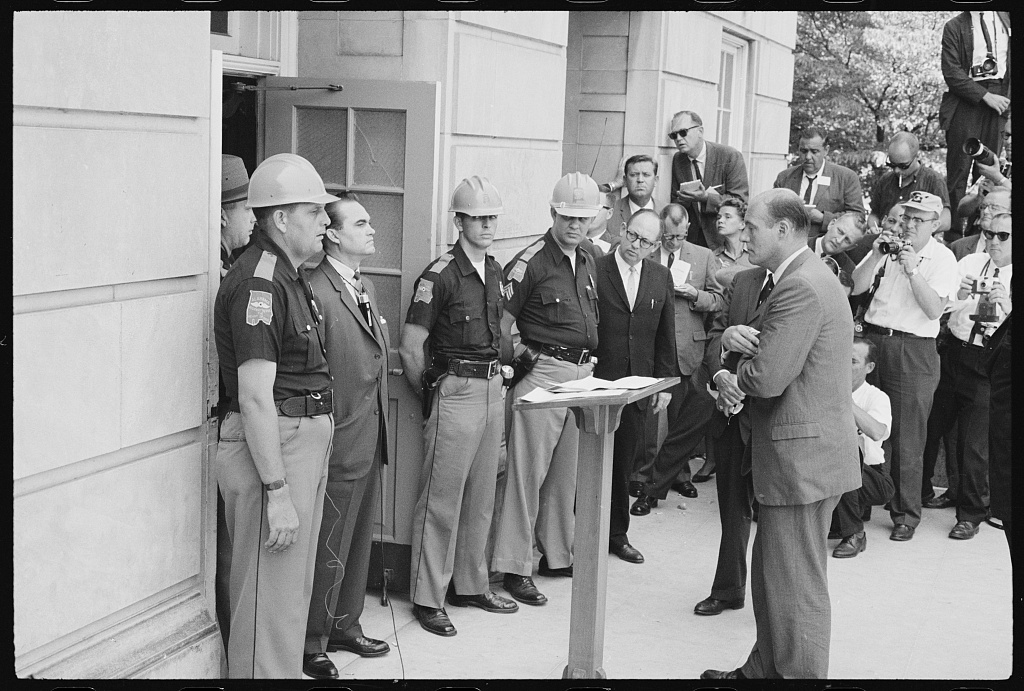

On the first day of her lesson sequence, Kellie Friend’s third grade class compared photographs of Jim Crow-era schools (Delano, 1941), read a picture book by Robert Coles (2010) about how Ruby Bridges integrated a New Orleans elementary school in 1960, and studied the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) and Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas (1954) Supreme Court decisions. Students spent time defining and using the words “segregation” and “integration,” and discussed the distinction between “integration” and “desegregation.”

“How do you think integrating schools worked?” Friend asked the class. “And how much time did it take to integrate schools? Discuss with a partner in your group and share.”

Two children near the front turned to each other. “To everybody, maybe it could have been a week or two to get out to everybody,” the first suggested. His classmate nodded, “And then another week or two to happen.”

“I feel like sometimes there’s a lot of misconceptions,” Friend said in an interview after the lesson. “That’s always a risk that you run, and you have to be prepared … You have to really be open for discussion.” Recognizing that her students had misconceptions, but not wanting to shut down the inquiry by centering herself as the “keeper of knowledge,” Friend instead introduced additional evidence, starting with a 1958 map (Segregation’s Citadel) showing the states where schools were still segregated, four years after the Brown v. Board decision. The map guided students to question their assumptions about the speed with which integration was achieved and the evolving status quo of segregation versus integration at the time. Then, Friend distributed a primary source set (Figure 2), containing images highlighting school integration in schools between 1955 and 1973. In small groups, the students analyzed one of the photos and completed a See-Think-Wonder chart to capture their observations, inferences, and questions (Friend, 2018).

Figure 2. Library of Congress Primary Sources Used in Third-Grade Lesson

On the final day of the lesson sequence, students investigated how school integration was implemented, and organized the primary source photographs they had previously examined in chronological order using only their deductive reasoning skills and short descriptions provided by the teacher (Friend, 2018). The photographs further pushed students to confront their assumptions about the Brown v. Board decision from the first day, suggesting that integration was not, as they had initially concluded, a change that happened overnight.

Friend continued to use primary source photographs as she moved forward in time and guided her students toward an interrogation of the status quo today. With students seated together, she showed them photos of schools in the Twin Cities metropolitan area today. According to the Minneapolis Star Tribune newspaper, urban schools in Minneapolis and St. Paul are among the least integrated in the Twin Cities, while the once overwhelmingly white suburban school districts (including the district Turtle Lake Elementary is a part of) are becoming increasingly diverse (Matos, Webster & Lonetree, 2015).

Students gazed up at the screen at a photograph of a St. Paul kindergarten class made up predominantly of students of color.

“Do they look integrated?” Friend asked.

Responses chorused from the group: “No. Yeah? Kind of…”

Friend showed students additional modern photographs of classrooms in Minnesota and in other states. She landed on a photo from the charter school that now occupies the site of the school Ruby Bridges integrated in 1960, depicting a class of entirely black students with a white teacher. Again, when asked, the students disagreed about whether or not it was integrated. The cognitive dissonance of their assumption that segregation had been “solved” was again evident in their conflicting responses.

“Yeah?” Friend said, repeating one student’s affirmative response. “Tell me how that’s integrated.”

One student in the front quietly raised her hand, eyebrows furrowed in concentration. “I don’t think … I don’t know why there’s like more black [students] than white.”

“That’s a good question,” responded Friend.

“I mean, Ruby Bridges did help change, but why couldn’t there be at least more white [students]?”

As the confusion about whether this classroom was integrated resolved into a collective “No,” students continued to comment on the photo, trying to figure out why it was not integrated.

“Maybe,” one student speculated, “a lot more black people moved to New Orleans because after Ruby Bridges became famous.”

“I think that there’s more black [students] at the school because a lot of black people feel a lot of pride going to that school because of what happened there,” another student adds.

Figure 3. Third-Grade Teacher Kellie Friend and Her Students

“It was a really big historical moment for black [people].”

“I don’t know,” Friend replied honestly. “Look at the research questions you’re making. You could research some of this.”

“This is what it should look like … maybe ten or twenty years before the Supreme Court made the decision that it was illegal to separate children,” a third student says. “This is a little like outdated or something like that.”

Friend let the students sit in the discomfort of their uncertainty, and did not direct them towards some sort of “correct” answer or try to make them feel better about the lack of comprehensive nation-wide school integration today. Instead, she closed the lesson for the day with a discussion around the question, “Are we better off today?” Students continued to examine and critique the status quo as they thoughtfully answered a question some might deem too sophisticated for third graders.

One child raised her hand. “Like, there probably still is … might be a little bit of segregation and they might be in other countries…”

Another student added, “Well, I’ve been to Florida and I still see a little segregation when I go there…”

A third student piped up. “The reason why I think segregation is still around is because some black football players kneel during the National Anthem.”

Friend tilted her head and asked, “Does that have to do with segregation or something different?”

“Well,” the student paused, his brow furrowed in concentration, “I think it means that they want black [people] to be treated fairly because I think they’re not technically being treated that fairly.”

At this point in the lesson, students drew connections between the historical content and the impact of historical struggles on society today. Suddenly, things like the National Anthem protests by Colin Kaepernick and other NFL players (Mather, 2019) fit into a narrative of racial struggle hundreds of years in the making that continues today. Using the historical knowledge they decoded, students began to “analyze how specific policies or citizen behaviors reflect ideals and practices consistent or inconsistent with democratic ideals,” (NCSS, p. 64) particularly, but not limited to, the context of de facto segregated schools and protests connected to the Black Lives Matter movement. By analyzing photographs and discussing to what degree we are all better off today, they measured the evidence shown to them, their own experiences, and evidence they’ve collected from the world around them against the American ideals of equality and fairness.

Friend capitalized on this by having students do some individual written reflection about things they want to change in the world as the closure to the lesson sequence.

Figure 4. Third Graders Analyze Primary Sources from the Library of Congress

There is No Age Limit to Participate in a Democracy

“I’m most happy about where they took a very difficult idea and were able to think critically, and bring it to today, even with their misconceptions.” (Friend, interview, Nov. 16, 2017)

Kellie Friend’s third graders did not walk out of her classroom having mastered all the skills they would need to call their representatives, stage a protest, or take some other immediate civic action. And the knowledge they had constructed was not complete, nor was it completely void of misconceptions. They had, however, practiced and improved their ability to “access, organize, and apply information from multiple sources reflecting multiple points of view” (NCSS, 2010, p. 64) through their engagement with both historical and modern primary and secondary sources. They also engaged in respectful and reflective discussions on “how specific policies or citizen behaviors reflect ideals and practices consistent or inconsistent with democratic ideals” (NCSS, 2010, p. 64).

“They need to examine their world critically. So, when people think that elementary students can’t do those things, I would say one hundred percent, they’re wrong.” (Friend, interview, Nov. 16, 2017)

These third graders developed foundational skills they used again and again throughout the school year and acquired foundational knowledge they will continue to build on and use to draw connections between the past and their world today. Later in the school year, Friend reported that these students were asking deeper and more critical questions, acknowledging competing viewpoints objectively, demanding evidence to support conclusions, reexamining and evaluating their own opinions, and calmly correcting mistakes and misconceptions (Friend interview, Feb. 14, 2019).

Successfully engaging in the historical inquiry process is a skill that takes a long time for students to practice and perfect. Their learning is not a destination of facts, but rather a skills journey to develop the ability to ask deep questions, collect and analyze sources, and communicate their findings. Trying to protect students from the difficult work of grappling with the issues of our time and the historical origins of those issues delays their ability to develop skills that are vital in the academic world, and indispensable to becoming active and discerning citizens.

As this classroom example shows, elementary students are often keenly aware of the issues and controversies swirling around them. With appropriate support and scaffolding, students can draw connections between the past and the present and use what they learn to examine and critique the status quo. Culturally relevant pedagogy provides a framework through which teachers can empower students to develop their critical thinking skills, regardless of their age or literacy level. In Friend’s lesson, selecting a topic directly relevant to students’ lives, like school, increased the likelihood that students would be engaged because the civic ideals of fairness, equality, and justice hit home when addressed in a familiar context. By drilling down on social studies topics significant to students’ lives, asking meaningful and challenging questions, and creating space for students to question and critique the world around them, teachers build spaces that are prime for developing civic ideals and practices.

“I think it’s important to teach in a culturally relevant way because they have to go out in this world. And if they only see what’s inside their classroom or inside their homes or their local communities, and don’t examine beyond that, we are not doing them the service that they need.” (Friend, interview, Nov. 16, 2017)

![[African American children on way to PS204, 82nd Street and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration]](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/service-pnp-cph-3c30000-3c34000-3c34400-3c34434v.jpg)

![[African American and white school children on a school bus, riding from the suburbs to an inner city school, Charlotte, North Carolina]](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/service-pnp-ds-00700-00762v.jpg)

![Little Rock, 1959. Mob marching from capitol to Central High / [JTB].](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/service-pnp-ppmsca-03000-03094v.jpg)

![[African American school children entering the Mary E. Branch School at S. Main Street and Griffin Boulevard, Farmville, Prince Edward County, Virginia]](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/service-pnp-ds-00800-00827v-e1702910366418.jpg)

![[Demonstrators marching in the street holding signs during the March on Washington, 1963] / MST.](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-ds-04000-04000v.webp)