By Kira Duke (Middle Tennessee State University)

Download PDF – Spring 2024, Article 2

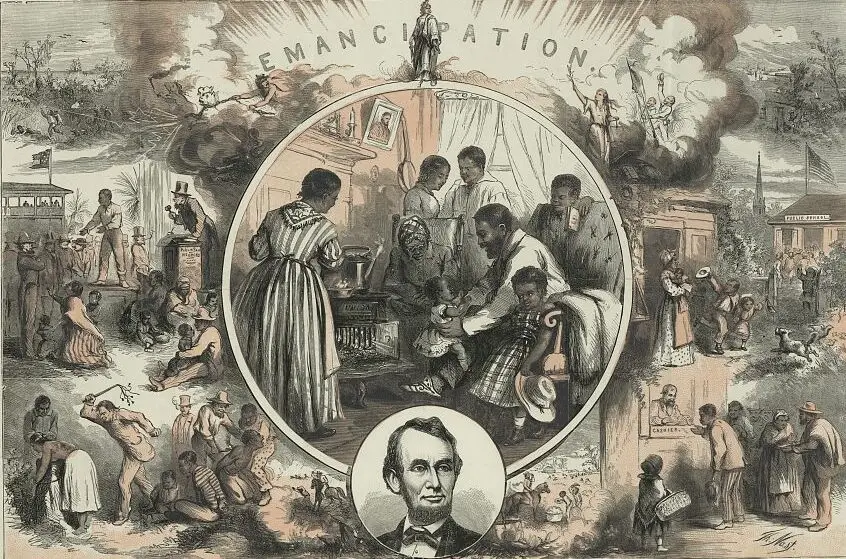

Bringing local history into classrooms offers a unique way to engage students and challenge the dominant narrative presented in our textbooks. Local history allows us to spark students’ curiosity about the people who built and shaped the communities in which they live and explore how communities have changed over time. Exploring stories of African American communities exposes students to a different way of thinking about the long arc of civil rights in this country. Local history centers the experiences of ordinary people, highlights the way people act and react to state and national events, and celebrates the humanity of individuals and the communities that they built. Incorporating local history gives educators access points for embedding the frameworks that were central to the Teaching with Primary Sources Civil Rights Fellowship (TPS CRF): King’s (2020) Black Historical Consciousness principles and Jeffries’s (2020) framework for teaching race and racism. In particular, a focus on community building and what happened to those communities is a way to highlight Black joy (King, 2020) and to Be Explicit – Personal vs. Structural (Jeffries, 2020).

After our study of the Reconstruction and Jim Crow eras, TPS CRF Fellows Connie Fink and Anna Stern, teachers at the University School of Nashville, began work on a lesson plan exploring the history of a post-Emancipation African American neighborhood near their school that was decimated by interstate construction in the mid-twentieth century. The Bass Street neighborhood, Nashville’s first post-Emancipation free Black community, was located beside Fort Negley, a Union fort constructed primarily by those who had fled enslavement and local free Blacks who were conscripted into service by the Union army. Fink and Stern’s lesson “Bass Street, Reconstruction Communities, and Memory,” written for eighth grade social studies and high school African American history classes, explores the questions: (a) How did Black people create communities during the Reconstruction and early Jim Crow periods?, (b) In what ways can “progress” shift the identity of a community?, and (c) How should we commemorate historic locations to preserve and perpetuate their stories and impact? The process, structure, and strategies of this lesson provide a model that other educators can follow to develop their own lesson plans centering local history.

One of the challenges of weaving local history into classroom lessons can be the availability of documented history for diverse and/or marginalized communities, especially communities that have been displaced. When Stern and Fink began work on this lesson, very little was documented about the history of Bass Street. To address this challenge, they pulled in materials from similar towns and neighborhoods to help students get a sense of what African American communities might have looked like during this period and then challenged students to apply their findings to the Bass Street neighborhood.

When looking for a point of comparison, educators should look for primary sources that can provide a broad range of comparisons by pulling in sources from various communities in the larger region. For example, Stern and Fink’s lesson begins with sharing images from the African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition collection that shows scenes from other neighborhoods in Nashville, as well as African American communities and businesses in Knoxville, Memphis, Chattanooga, and Atlanta.

Selected images of churches, schools, homes, and businesses, especially those from your state or region, give students a starting point to build their understanding of what African American communities looked like during this time. When analyzing the images, ask students what institutions served as the foundations for a community. For instance, almost every Reconstruction and post-Reconstruction Black community was centered around places of worship, schools, and cemeteries (Tinker, 2023; West, 2016). Therefore, selecting primary sources that reflect the importance of those institutions is a good first step to helping students understand Reconstruction-era communities.

Another approach to addressing the challenge of finding documented histories for local communities is to incorporate materials from a single community where primary sources and a general history are available and accessible to your students. For example, Stern and Fink’s lesson asks students to explore the Cemetery community, located about fifty miles southeast of Nashville in Rutherford County, on the edge of Stones River National Battlefield. Cemetery’s history has been well-documented in recent years through various public history projects facilitated by Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU)’s Center for Historic Preservation and the MTSU Public History program. Furthermore, Cemetery serves as a good point of comparison for Bass Street as both were founded near key Civil War military sites, and both communities were created by people who had moved to the specific area for war-related work with the Union army. Using Cemetery as their point of comparison, students were then prepared to explore and identify similar patterns experienced by the Bass Street community.

If educators need assistance identifying communities and their histories in their geographic area, they can check with local historical societies, universities, museums, and archives for resources. Many of these organizations welcome opportunities to share their work with educators and their students.

With a solid understanding of what other African American communities looked like in the area, students are now ready to begin exploring the Bass Street community and creating their historical interpretation of what this community looked like and its impact. Students are tasked with analyzing a combination of Sanborn maps, newspapers from Chronicling America, federal census records, and archaeological findings to answer their investigative questions.

Sanborn maps are especially useful for exploring local history. These fire insurance maps were created beginning in the late 1860s. They provide detailed depictions of industrial, commercial, and residential areas of cities throughout North America. They tell us about all the buildings in a community, including what type of materials were used to construct a building and what its purpose was. They include property lines and street names. Sanborn maps are a fantastic primary source for digging into local history, since they show us where people lived, worked, shopped, and worshiped.

Sanborn maps are especially useful for exploring local history. These fire insurance maps were created beginning in the late 1860s. They provide detailed depictions of industrial, commercial, and residential areas of cities throughout North America. They tell us about all the buildings in a community, including what type of materials were used to construct a building and what its purpose was. They include property lines and street names. Sanborn maps are a fantastic primary source for digging into local history, since they show us where people lived, worked, shopped, and worshiped.

Layering Sanborn maps with other primary sources, such as census records and local newspapers, can give us a rich look into any community. The Chronicling America historic newspapers online collection is a treasure trove for anyone looking for historic newspapers from across the United States. Through the collection’s homepage, you can search by state, ethnicity of the paper, and date. For this lesson plan, articles from the Nashville Globe, a Black-owned and operated newspaper that ran from 1906 into the 1930s, were selected, including death announcements, a Santa letter, a marriage announcement, and two recaps of dinner parties. Students are challenged to read and analyze these articles to determine what life was like in the neighborhood. Additionally, you may seek out local oral histories that can be shared with your students to further humanize a community. Exposing students to an array of available primary sources will help them connect to the individuals who lived in the community and see how these people experienced life.

An exploration of local history can be a great way to incorporate a more diverse range of voices in your instruction. Local history can show students how ordinary people experienced the big events highlighted in textbooks and how they helped shape those events. In this lesson, students walk away with a glimpse of how residents in this one African American community in Nashville experienced life in the midst of the Jim Crow period. That glimpse centers the people of Bass Street and uplifts Black joy while at the same time explicitly showing what life in a segregated city in the South looked like during this time. Fink and Stern’s lesson plan concludes with a challenge for students to reflect on how we preserve the histories of different people and communities. Local history can challenge us to struggle with the question of whose history we deem significant enough to save. Incorporating local stories into your teaching can empower students to play a role in preserving those histories and broaden their learning beyond the dominant narrative of the civil rights movement.

References

Jeffries, H. K. (Ed.). (2019). Understanding and teaching the Civil Rights Movement.

University of Wisconsin Press.

King, L. J. (2020). Black history is not American history: Toward a framework of Black

historical consciousness. Social Education, 84(6), 335–341.

Tinker, N. C. (2018, March 1). Rural African American Church Project. Tennessee Encyclopedia. https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/rural-african-american-church-project/

West, C. V. (2016). Preserving African American historic places: Suggestions and sources. MTSU Center for Historic Preservation. https://irp.cdn-website.com/2c253136/files/uploaded/Preserving-African-American-Historic-Places.pdf.

![[Demonstrators marching in the street holding signs during the March on Washington, 1963] / MST.](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-ds-04000-04000v.webp)