By Kelly Jones-Wagy, Peggy O’Neill-Jones, and Linda Sargent Wood

Download PDF – Volume 1, Issue 1, Spring 2021, Article 1

As a high school social studies teacher for the past thirteen years, I have worked with students on analyzing historical primary sources, but it also is essential that students understand that analysis applies to more than just historical documents. Two first-hand accounts illustrate why. In the spring of 2018, students burst into my classroom to show me a YouTube video exclaiming, “Mrs. Jones-Wagy, you’ve gotta see this!” They had a video claiming that the recent California wildfires were started because the government was testing a new laser weapon.

A few months later, another group of students announced that the CIA executed American rapper Nipsey Hussle, contending that Hussle had proof that the U.S. government kept a secret HIV/ AIDS cure from the public in the 1980s, so the CIA had to stop him.

After each of these incidents, I spent a significant amount of class time walking the students through why these stories were not accurate and how to assess them for credibility. I explained the concepts of bias, author, perspective, evidence, and reasoning, until they realized that, once they dug below the surface, the stories lacked credibility. I know I am not alone in experiencing the difficulty students have in evaluating the validity of social media, and it is essential to our democracy that they learn to interrogate the claims of social media just as we ask them to do with any other source. In this article, I team with two of my colleagues in history education to explore a few ways we can help this generation apply historical literacy skills to the contemporary world of social media.

Social media is not just about mindlessly watching funny cat videos; social media offers many online forums and communities for people to share ideas, information, and opinions. Often these electronic forms of communication have facilitated positive civil discourse, but social media has also become—as many of us have painfully discovered—a vehicle for disseminating false stories, deceptive innuendos, and fake videos. We all need to be much more aware of who is contributing to the conversation and educators need to teach students to exercise the same critical thinking skills when reading a Twitter thread as they do in reading the U.S. Constitution.

Educators teach students to ask critical questions about a text. Such questions include an examination of an author’s purpose, bias, perspective, and intent as well as close reading for factual accuracy, context, and corroborating evidence. These are fundamental to critical reading and to an informed public. This work, when applied to the discipline of history and primary source analysis, can dispel common misconceptions.

For example, students can learn that some of the popular myths about George Washington, spread through popular forums like a 1913 Puck publication that shows Washington with his cherry tree (Glackens, 1913), are not true. The Mount Vernon website states that the cherry tree story is a myth created by his biographer (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2019a). George Washington had no cherry tree and his teeth were not made of wood (George Washington’s Mount Vernon, 2019b).

Finding and dispelling misinformation on social media is a difficult, though not impossible, task. Too often, educators have assumed that because students were born in the age of the Internet that they know how to use it, but in reality, their formal education has no more equipped them to use social media for reliable information than it has prepared them to use a butter churn. Helping them apply sleuthing skills to detect accuracy of a source is paramount to a thriving democracy.

Finding reliable, credible sources of information is but one of the challenges for this age. Sharing and communicating via social media is also part of the mix. As educators, it is our responsibility to teach students that they must not only be savvy consumers but also responsible users and producers. Students can be misled in reading a post or watching a video. Sharing information must also be done with care— and not too fast. Hitting the pause button to verify and corroborate something is smart no matter the medium. Learning to do that when the communication channels move quickly is fundamental.

To exercise good citizenship and be good community members, individuals need to be responsible users and producers of social media. Our posts matter. Our words and conversations have consequences. What we tweet and retweet must be considered and measured. It is our individual and civic responsibility to develop the skills to carry on civil and reasonable communication, to spot and call out misinformation (false information) and disinformation (false information with a malicious intent) so that we are not duped and that our neighbors are not either.

So how do teachers help students recognize the need to apply the same critical thinking skills to social media sources that they do to primary sources? This article makes the case that teachers need to help students apply the same analytical tools they have used to understand, explain, and critique primary sources to Tweets, Instagram photos, Snapchats, and YouTube videos. While training students in critical thinking and academic literacy is important and essential to many subjects, it is the essence of the historical discipline to take on the responsibility of teaching social media and civic engagement in the social studies classroom as primary sources of the 21st century.

History teachers regularly ask students to source documents. Students learn to read for authorship, purpose, bias, context, format, and intended and actual audiences. These same skills can equip learners for the world of social media, and teachers should give them practice doing so. In this way, this article builds upon the work that Sam Wineburg and others are doing through the Stanford History Education Group Online Civic Reasoning (Wineburg, 2019). Relying primarily on tried lessons in Jones-Wagy’s high school classroom, we offer several teaching tips and tools to help students become more critical consumers and savvy producers of social media. In the end, we hope this helps foster a more informed citizenry.

Characteristics of Social Media

To teach the skills of source analysis within social media, it is important to recognize that 21st century electronic media comes to us in a variety of formats and creates a dynamic space for engagement and communication via our various phones and devices that access the Internet. It involves multiple media types we are all familiar with, including text, audio, video, and images with added social components—commenting, posting, sharing, and liking—that promote a dynamic conversation. Creators of and participants on social media choose the electronic platform by which to send and receive information such as Twitter, YouTube, Instagram, or Facebook. A conversation on social media may be short and limited to select followers or go viral, hitting wide audiences.

The key to understanding the ways social media can affect an academic approach to research includes how it can create echo chambers (user’s choice) and filter bubbles, which are created for the user by algorithms (technology generated). In other words, an individual can follow news organizations with a particular bias, creating an echo chamber, in which comfortable and familiar ideas are reinforced. What makes a social media forum particularly isolating is that platform can reinforce the message through an algorithm that queues similar content to what the user has interacted with previously. Social media can foster spaces where users choose only information that supports and reinforces their beliefs and perspectives.

Another key difference between social media and other sources is the speed of information that is available. Imagine if President Franklin Delano Roosevelt delivered his fireside chats to the nation today. It would not come synchronously through the crackling sound waves of the radio. FDR might offer a weekly asynchronous podcast. In addition to the official telegram informing FDR about the attack on Pearl Harbor, he might have initially received informal, unconfirmed rumors via Snapchat before the telegram arrived. No longer does one have to wait for the nightly news. For example, a June 14, 2019 5:25 a.m. ET Wall Street Journal headline states U.S. Says Tehran Is to Blame for Attacks on Fuel Tankers (McBride, Jones, Faucon, & Paris, 2019). A June 14, 2019 7:30 p.m. MDT NBC News headline states Japanese Tanker Owner Contradicts U.S. Officials over Explosives Used in Gulf of Oman Attack (Givetash & Yamamoto, 2019).

Within social media, individuals can participate as consumers and producers. Social media consumers visit or subscribe to a platform, such as YouTube, to view the content. But social media is not designed to be a one-way communication. Instead, it invites conversation. Consumers become social media producers when they respond to or comment on content they see or view or when they create content. In many ways, social media further democratizes communication, allowing any individual or group to publish content.

Information flies at lightning speed with global access, and fast-moving dialogue makes it easy not to consider other voices and points of view. Response is quick; mistakes are easy. Thus, the challenge for teachers: we know living in filter bubbles and echo chambers can prevent us from participating in a full civic dialogue that includes understanding of and empathy for other perspectives. Helping students become aware of the algorithm is half of the battle. Educators also need to provide students with the abilities to counteract the algorithms. Primary source analysis tools can expose this and aid students in asking questions related to the characteristics of a medium, i.e., text, video, audio. Social media is just another format with its distinct characteristics.

Teaching Tools

Below are examples from Kelly Jones-Wagy’s high school classroom that illustrate the importance of teaching students to use primary source analysis skills to become critical consumers of social media. In addition, this lesson helps students reflect on their individual perspectives and consider how their biases may influence their choices when they act as social media producers.

Teaching Tool 1, “Exposing the Filter Bubble,” is a short activity to help illustrate how social media creates a filter bubble and to help students use critical thinking skills in regards to social media. Many times, students are tempted to click on the first search result when they type something into the Googlea search engine. Once they become aware that the first result for them may be different from the person next to them, students are then able to start asking questions about what they are seeing, and perhaps more importantly, what they are not seeing.

Teaching Tool 2, “Sourcing Social Media,” contains three strategies for sourcing social media. Strategy A is a chart that helps students see how today’s social media is similar to twentieth- century media. Students use a primary source analysis tool to look for contextual clues (e.g., names, dates, author) on a twentieth-century source and use the same tool on a similar social media source. For example, students analyze a telegram and a Tweet. To move into higher-level thinking skills, there are two additional teaching strategies. Strategy B helps students to identify bias in the media. Students visit a series of news sites and compare them based on the types of stories that are covered, the language used, and the layout of the website. Students then compare different news sites to see how bias can change the way the same event is being described. Strategy C asks students to move into the highest levels of Bloom’s taxonomy. Students use critical thinking skills to analyze an online news source. They evaluate the gray areas of social media, where sources are not always credible, but are not fake. These sources are somewhere in between.

Teaching Tool 3 asks students to reflect on their learning of social media and use their skills to understand their role as a social media producer.

Teaching Tool 1:

Exposing the Filter Bubble

- Essential Question: How do you get out of the filter bubble?

- Problem: Students don’t understand that they have been isolated in a social media filter bubble.

- Skill: Contextualization; seeing the context; identifying perspective (Newland, 2014).

Many students are unaware that they have either self-isolated or that technology algorithms isolated their access to information.

It is important for them to understand that this creates an echo-chamber effect and compromises their perspective on understanding an issue or story. It is impossible for students to look outside their bubble if they are unaware that they are inside of one.

In order to get students to start thinking critically about the Internet and the role of social media, it is important to go beyond the first page of an individual’s Google search results. Political activist Eli Pariser’s TED Talk, “The Filter Bubble” (Pariser, 2011), explains this introductory activity. At three minutes, twenty seconds into the video, pause to ask students to conduct Pariser’s experiment: Ask students to pull out their phones, open a browser, and type in “Egypt,” then compare results with a neighbor. Typically, students glance at their results and see that there are similarities, but when asked to examine their results in comparison with their neighbors’, or the teacher’s, they discover distinct differences. Sometimes their searches yield different news headlines or stories from competing outlets.

Many times, results present in different orders or rankings. The teacher should engage students in a discussion of the differences, then inquire, “What might cause these differences?”

Continue playing the TED talk to hear Pariser explain that search engines contain algorithms that personalize information and select material that conforms to what it appears an individual wants. This can feed filter bubbles, leaving us cocooned within select spheres and bereft of multiple perspectives and ideas. When the TED talk is completed, ask students to brainstorm ways to avoid the filter bubble. Get students to formulate questions they can use to determine how to find out what they don’t know.

Teaching Tool 2:

Sourcing Social Media – Strategies A, B, and C

- Essential Question: How do you determine what is reliable on social media?

- Problem: Since there is so much information at our fingertips, how do educators help students sort through available information to determine credibility, reliability, author intent, perspective, bias, etc.?

- Skill: Sourcing (Wineburg, 2010)

As educators, we should urge students to question the source, whether it is of yesterday or today, whether online or not. Who produced it? What is the message? Why was it produced? What is the agenda? Who is the intended audience? Why? Because of the interactive nature of social media, we also need to get students to ask, who is responding to a post?

Who else is participating in the forum? What is their message and intention? Questions should push an analysis of the importance, relevance, and accuracy of the content and message construction, setting it within the historical or contemporary context, examining its outcomes.

In the following three teaching activities, sourcing skills are employed at different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy. The first asks students to identify basic information such as the 5 W’s including who, what, where, when and why as well as the 5C’s of historical reasoning as noted by historians Thomas Andrews and Flannery Burke: change over time, context, causality, contingency, and complexity (Andrews & Burke, 2007). In the second activity, students examine bias in online media, and in the third, students question source credibility using inquiry methods and critical thinking skills.

Strategy A: Analyzing 20th Century Sources and Social Media Sources

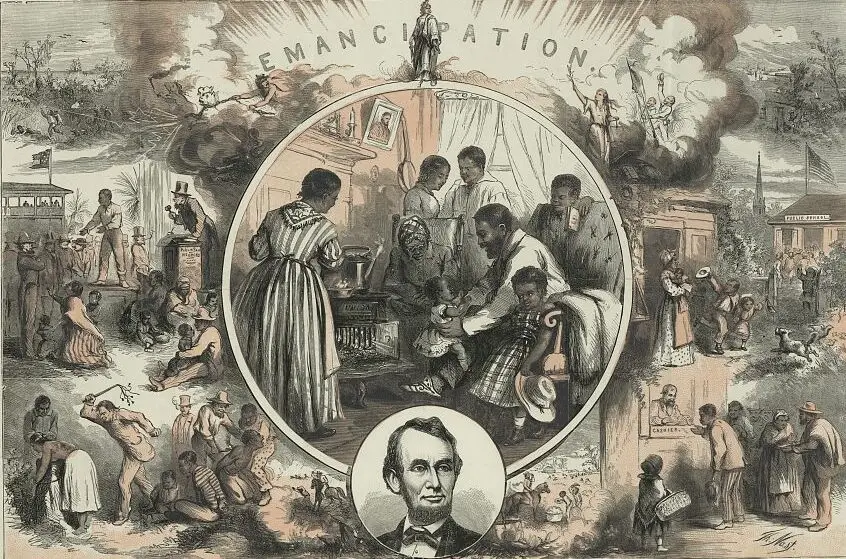

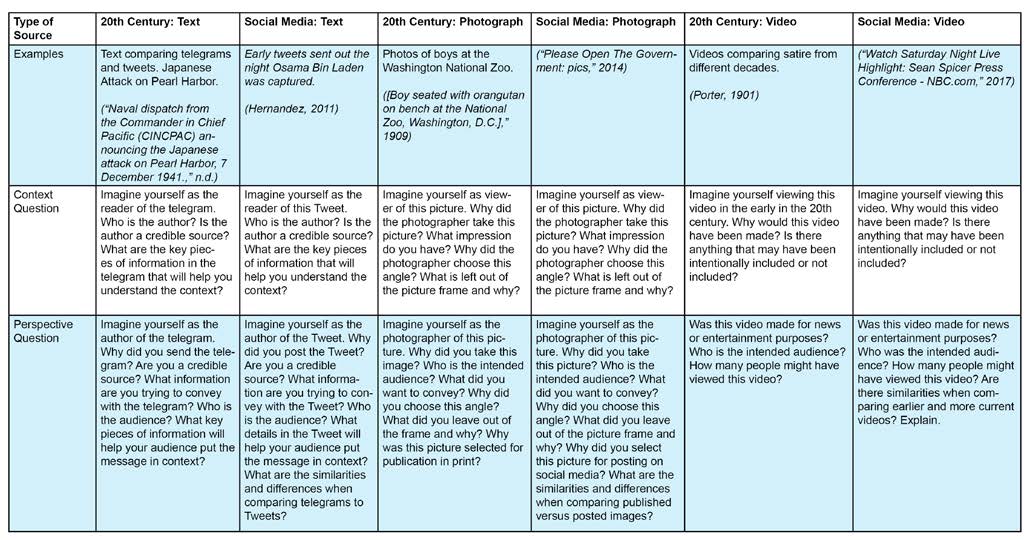

This activity asks students to examine three types of sources: a short text, a photograph, and a video. In Figure 1 below, six sources are set out side by side. Three are from the 20th century and three are social media postings from the past decade. Students analyze each and compare and contrast the different media types. Since many history students are familiar with analyzing historical sources, students first gather information about the 20th century sources, including dates, names, places, authors, and publishers. They are then asked to transfer that skill and ask the same questions of the more current social media sources (See Figure 1).

All the sources are investigated using a primary source analysis tool such as the one available at the Library of Congress, which accommodates a variety of media types (See Figure 2). Students interrogate each source by what they observe, what they reflect and wonder about, and what questions for further investigation the source generates. Once they have completed an analysis of the source, they answer specific questions about context and perspective related to each type of source, whether a text, photograph, or video, to help them critically analyze social media.

Figure 1. Analyzing 20th Century Sources and Social Media Sources

Figure 2. Primary Source Analysis Tool from the Library of Congress

Strategy B: Bias in the media

There are many primary sources that show bias. This does not necessarily discount the source. Rather, a recognition of the bias and perspective helps build a complete narrative of a historical event or person. This activity is designed to help students identify bias through structure, language, and content from news websites on a local, national, and global scale (See Table 1).

Table 1

Teaching Tool: Questions for Media Websites

- Go to the CNN, FOX News, and the BBC websites. What are the headline stories? How do these stories differ from one another?

- What other stories are covered on the websites? How is the order of these stories different in each website?

- Are there stories that show liberal or conservative bias? What are they? What is the evidence of bias?

- Go to your local news station. What stories are covered? What are the differences between the local, national (CNN, FOX), and world (BBC) news?

- Pick one of the websites and examine it for structural bias. Is there a bias in the kinds of stories that are covered? What is this bias? What is your evidence of this bias?

- Scan a story on FOX News and CNN. Be sure that it is the same story. Look for differences in language, in how people are described, in tone, and content. Note the location of the story on the website. What does the language chosen and the placement of the story tell you about the bias?

(Waples, 2014)

Strategy C: Analyzing Websites

The final activity on sourcing requires students to draw inferences based on the information they can gather. Students are asked to read an adapted version of Tips for Analyzing News Sources from Melissa Zimdars, an Assistant Professor of Communication and Media at Merrimack College. The entire document can be viewed on a Google Doc created as a resource for her students (Zimdars, 2016). This activity asks students to explore the gray area of social media (See Table 2).

Table 2

Teaching Tool: Source Credibility

Use the information provided at Zimdars’s website: https://bit.ly/360iqZl

- Use Google to look up a topic in history that you are interested in that could be considered controversial. Complete the information below and be prepared to present to the class

- Article Title

- Website URL:

- Look at the Steps for Analyzing Websites. Are there any clues to the credibility of the website?

- Summarize the article:

- Using the Website Labels, what are the tags for your website?

(Zimdars, 2016)

Students are still generally taught that websites that end in .org are credible, and they search Google Images for information, because reading the search results in a regular Google search takes too long. As they go through these exercises, students begin to understand that the answers they find on the Internet are full of gray areas. There are right and wrong answers, but there are also opinions, clickbait, satire, misinformation, disinformation, political bias, and false information. This activity asks students to ask questions about their sources. Do they link to corroborating evidence? Who are the authors and publishers? What clues on the website or in the story reveal author intent, bias, perspective?

Teaching Tool 3:

Producing and Contributing to Social Media

- Essential question: How do we contribute to social media responsibly?

- Problem: If we ask students to be critical consumers who source for credibility and reliability, we also need to help students be responsible producers whose messages are trustworthy, authentic, sensible, and effective.

- Skill: Communication skills; create an effective, self-aware social media message.

Table 3

Teaching Tool: Social Media Producer

Ask students to produce a social media post and analyze it using a primary source analysis process.

I want to communicate ___(content)___ to ___(audience)___.

- As the author of the post, who am I? What are my biases and points of view?

- As the author of the post, what is my agenda?

- Who is my audience?

- What are my sources? Are my sources credible and reliable? Do they provide evidence for my claims?

- How do I want my post to affect my audience?

- Why am I choosing this medium to communicate my message?

- Why did I choose this social media platform to communicate my message? (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube)

- Who do I think this social media post will be shared with?

- What consequences do you anticipate if others share your social media post on their networks?

This teaching idea focuses on developing responsible practices on social media. After helping students be critical consumers of social media, the goal with this activity is to help students create meaningful, reliable, credible, and effective communication using social media. In essence, it flips what we have required students to do as critical consumers and asks them to interrogate themselves and their own social media messages, questioning their motive, agenda, perspective, and work. It asks them to check their content to make sure it is accurate, evidence-based, and logical. It requires students to consider their audience and how they might be most effective in communicating via social media (See Table 3). as we recognize that social media is not just a benign tool to engage students in learning and presenting their work (National Council for the Social Studies, 2018). Social media wields powers both inside and outside the borders of the United States. As technology company CEOs testify before Congress about the security of their platforms, the advertisements they have sold, and the ways that fake news has spread, it is becoming more and more obvious that the classroom must bear some of the burdens for educating individuals in how to critically read what is before them on social media, and how to be responsible citizens on these changing communication platforms.

Things are moving quickly, and we are cognizant that communication technology evolves and that news feeds shift by the minute, but the importance of analysis and teaching students to be wise consumers and trustworthy civic participants remain.

It is essential to the workings of our democracy to equip students with shrewd and discerning analytical skills so that they are not misled by millions of bots and disinformation campaigns. After finding that many secondary and college students lacked the ability to detect fake news on social media, educational psychologist Sam Wineburg and his research team concluded that many of us need to go to fact-checking school (Wineburg & Reisman, 2015). Fortunately, what we have learned in teaching primary source analysis gives us the building blocks to equip these students.

Students in this technologically-based world use social media as part of day to day life. However, they must be taught not only how to consume judiciously but also how to produce thoughtfully. This calls for critical thinking, source analysis, and seeing the connections and pitfalls in social media’s collaborative network.

Conclusion

Becoming critical consumers and producers of social media is particularly relevant today as we learn daily about the influences and effects of social media on our everyday lives. Classroom discussions have shifted and become weightier

Authors

Kelly Jones-Wagy teaches U.S. history, American government, comparative government, and other social studies classes at Overland High School, in Colorado. In 2019, Kelly received the Governor of Colorado’s Civic Educator of the Year Award and was named Street Law Inc.’s Educator of the Year.

Peggy O’Neill-Jones, Ed.D., is professor emeritus at Metropolitan State University of Denver’s School of Journalism and Media Production. She directs the TPS- Western Region, and the TPS Teachers Network, on behalf of the Library of Congress.

Linda Sargent Wood, Ph.D., is an associate professor at Northern Arizona University, Department of History. She teaches courses on American culture, the historical inquiry process, and history education. Linda is a recipient of a 2011 TPS Western regional grant.

References

Andrews, T., & Burke, F. (2007, January). What does it mean to think historically? Perspectives in History. https://www.historians.org/publications- and-directories/perspectives-on-history/january-2007/what-does-it-mean-to-think- historically

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. (2019a). Cherry tree myth. Retrieved August 25, 2019, from https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/cherry-tree-myth

George Washington’s Mount Vernon. (2019b). False teeth. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/false-teeth

Givetash, L., & Yamamoto, A. (2019, June 14). Japanese tanker owner contradicts U.S. officials over explosives used in Gulf of Oman attack. NBC News. Retrieved from https://www.nbcnews.com/news/world/japanese-tanker-owner-contradict-u-s-officials-over-explosives-used-n1017556

Glackens, L. M. (1913, February). He had a hunch. Puck. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/ item/2011649439

McBride, C., Jones, R., Faucon, B., & Paris, C. (2019, June 14). U.S. says Tehran is to blame for attacks on fuel tankers. Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from https://www.wsj.com/articles/ reports-of-incident-in-gulf-of-oman-send-oil- prices-up-11560410373

National Council for the Social Studies. (2018). Youth, social media, and digital civic engagement. https://www.socialstudies.org/positions/youth- social-media-and-digital-civic-engagement

Newland, R. (2014). Primary sources and research part II: Sourcing and contextualizing to strengthen analysis. Teaching with the Library of Congress. Retrieved November 25, 2019, from https://blogs.loc.gov/teachers/2014/03/primary- sources-and-research-part-ii-sourcing-and- contextualizing-to-strengthen-analysis

Pariser, E. (2011). Eli Pariser: Beware online “filter bubbles.” Retrieved January 24, 2019, from http:// www.ted.com/talks/eli_pariser_beware_online_ filter_bubbles.html

Waples, K. (2014). Personal communication.

Wineburg, S. (2010). Thinking like a historian. Teaching with Primary Sources Quarterly, 3(1), 2–5.

Wineburg, S. (2019). Civic online reasoning. Retrieved June 14, 2019, from https://sheg.stanford.edu/civic-online-reasoning

Wineburg, S., & Reisman, A. (2015). Disciplinary literacy in history: A toolkit for digital citizenship. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy. https://doi.org/10.1002/jaal.410

Zimdars, M. (2016). False, misleading, clickbait-y, and/or satirical “news” sources. Retrieved June 14, 2019, from https://bit.ly/360iqZl

![[African American men, women and children outside of church]](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-cph-3c00000-3c03000-3c03300-3c03393v-e1708980496747.webp)