By Daniella Ann Cook (University of South Carolina), Kira Duke (Middle Tennessee State University), Bridget Morton (Mars Hill University), and Jenna Spiering (University of South Carolina)

Download PDF – Spring 2024, Article 1

An essential goal for all educators is to cultivate our – and our students’ – capacity simply to stay in the difficult conversation and avoid the temptation to water down, avoid, or run away altogether.

– Stephen Thurston Oliver

Though all state standards address teaching the civil rights movement (CRM), the standards often contribute to misrepresentations and misunderstandings of the movement (Anderson, 2013). Aligning with American academic and popular culture, many standards continue to reinforce a top-down, naive approach that focuses the definitive roots of the movement with national actors (e.g., Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks) and actions (e.g., the March on Washington) (Jeffries, 2019; Aldridge, 2006). Charged with teaching the standards, educators play a crucial role in teaching the civil rights movement accurately. Educators’ enhanced understanding of the CRM can help them teach a more nuanced history that addresses the role of race and institutional racism (Aldridge, 2006; Anderson, 2013; Jeffries, 2020; Payne, 2006; View, 2004).

Rather than relegating the CRM to a simple exploration of the past, robust explorations of the movement provide meaningful opportunities for learners to make connections between the experiences of people in their local and state communities with those in the larger movement. Not only does this provide ways for students to see themselves and their communities in the movement for civil rights, but this approach also furthers civic engagement. Indeed, Black communities’ agency, seen in the myriad ways people responded to racial discrimination, demonstrated over and over again how to be civically engaged. When students learn about racism and discriminatory practices using primary sources (e.g., oral histories of community and family members), and place-based learning opportunities (e.g., visits to cultural heritage institutions and sites), they also learn about strategies ordinary people used to combat oppression in the past and the potential for strategic action against oppression in the current moment. In this way, studying the social issues underpinning the long civil rights movement encourages social activism as civic engagement in a multiracial democracy.

Drawing on experiences from a two-year Teaching with Primary Sources Civil Rights Fellowship (TPS CRF) professional development program (fall 2020-summer 2022), this issue examines the importance of teaching the civil rights movement accurately with an explicit focus on equipping educators to do so using primary sources from the Library of Congress, as well as from state and local archives.

Our Partnership: Teaching with Primary Sources Civil Rights Fellowship

Reframing teaching the CRM as a human rights movement allows teachers, and learners, to connect with the larger equity and power issues that the movement sought to address and redress. The TPS CRF is a collaboration among three TPS Consortium members: Mars Hill University (MHU), Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU), and University of South Carolina (USC). Eighteen K-12 educators (Fellows) from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee committed to studying the long civil rights movement in the United States. Aligning with our interdisciplinary commitments, the Fellows included classroom teachers and school librarians. Collectively, the aim of the professional development was threefold: (a) center the long civil rights movement beyond the eleven-year period, 1954-1965, to demonstrate the span of the Black freedom struggle, (b) highlight the important role of local and state organizing for civil rights, and (c) honor the contributions of countless ordinary people to the movement.

Reframing teaching the CRM as a human rights movement allows teachers, and learners, to connect with the larger equity and power issues that the movement sought to address and redress. The TPS CRF is a collaboration among three TPS Consortium members: Mars Hill University (MHU), Middle Tennessee State University (MTSU), and University of South Carolina (USC). Eighteen K-12 educators (Fellows) from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Tennessee committed to studying the long civil rights movement in the United States. Aligning with our interdisciplinary commitments, the Fellows included classroom teachers and school librarians. Collectively, the aim of the professional development was threefold: (a) center the long civil rights movement beyond the eleven-year period, 1954-1965, to demonstrate the span of the Black freedom struggle, (b) highlight the important role of local and state organizing for civil rights, and (c) honor the contributions of countless ordinary people to the movement.

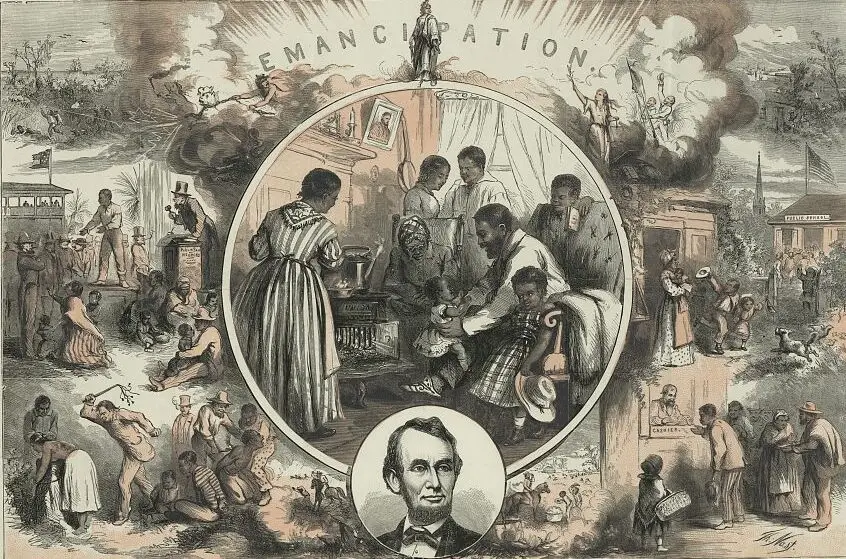

Drawing on different sites in the American South, the TPS CRF used primary sources with place-based activities that were interdisciplinary explorations connecting historical thinking skills with other social studies disciplines, such as economics and geography. The TPS CRF Consortium members focused on three distinct periods – American Slavery (MHU), Jim Crow (MTSU) and the Modern Movement (USC) – to debunk common misunderstandings and highlight important concepts for learners to access historically rich and nuanced perspectives from their respective period. Engagement with local history was greatly enhanced by the Library’s digital collections, specifically the Gladstone Collection of African American Photographs, Civil Rights History Project, and The Civil Rights Act of 1964: A Long Struggle for Freedom. In partnership with Auburn Avenue Research Library, the TPS CRF’s culminating professional learning conference was held July 7-8, 2022 in Atlanta, GA and included a keynote by Charles Payne, an interactive arts performance facilitated by Alliance Theater, concurrent sessions by TPS Consortium members, and site visits to the Apex Museum, the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Park, and the National Center for Civil and Human Rights. This approach captured the complexity and contours of the movement.

The TPS CRF Consortium members were intentional about countering the dominant narrative of the movement, which casts it as an 11-year (1954-1965) period of events led by charismatic national leaders. The type of deep learning we cultivated required paying attention to how we modeled culturally relevant approaches so that participants would be able to do the same with their students. Secondly, similar to challenges faced by teachers, we had to be mindful of the Fellows’ varying degrees of knowledge about the CRM and skill levels in discussing race and racism. Finally, we concur with scholars (e.g., Hasan Jeffries), and practitioners (e.g., Learning for Justice) that race neutral understandings are not enough for cultivating the skills and knowledge necessary to learn and teach history.

Our Approach: Teaching the Civil Rights Movement

As teachers, we are dutybound to provide students the unvarnished truth. And the times in which we live demand that we do so. To do anything less is to commit educational malpractice. (Jeffries, 2019, p. xiv)

Since the TPS CRF was not limited by the constraints of traditional classrooms, we enacted different possibilities of what could be done with educators interested in a deeper engagement with the movement. We were committed to “grappling with the ‘structured blind-nesses’ in [the] national fable – to see the ways the stories they tell and the elements they leave out and distort are perilous for our present” (Jeffries, 2019, p. xvi). The initial activity served dual purposes: (a) begin community building among and with the Fellows and (b) assess prior knowledge about the civil rights movement. To introduce themselves to the group, we asked the Fellows to post a primary source they used to teach the CRM to a video sharing app. Many of the sources they selected were from Library of Congress online exhibitions or collections, such as The Rosa Parks Collection, Chronicling America, The Civil Rights Movement Primary Source Set, and Free to Use: African American Women Changemakers. During our first virtual meeting, the Fellows discussed the meaning of the selected sources as a way to engage their existing narratives of the movement. During this introduction, the TPS CRF Consortium members foregrounded our commitment to thinking about the CRM in ways that allowed for complexity and depth.

In subsequent virtual synchronous and asynchronous sessions, the Fellows engaged with texts (i.e., Reynolds & Kendi Stamped from the Beginning; Jeffries, Understanding and Teaching the Civil Rights Movement) and scholars (e.g., Tina Heafner; LaGarrett King; Jenice View) to lay the conceptual foundation for historically robust learning about the long arc of the civil rights movement. Heafner (2020) explored connections between the long arc of civil rights and contemporary social issues using primary sources. Drawing on her work with Deborah Menkart and Alana Murray (2004), View (2022) offered ways for the Fellows to address gaps in traditional understandings of the CRM using six lenses: women, youth, organizing, culture, institutional racism, and the interconnectedness of social movements. The six-lens framework debunks common misunderstandings of the CRM which identify, for instance, integration as its primary goal and the federal government as one of its champions. Heafner and View highlighted oft-ignored events (e.g., Columbus landing on islands – Puerto Rico and U.S. Virgin Islands – in 1493) and civil rights issues articulated by ‘allies for justice’ (Heafner, 2020), such as the account by Bartolome de las Casas regarding Spain’s massacre and enslavement of indigenous peoples. Further examples offered for a more complete understanding of the CRM include Frederick Douglass’ support of women’s suffrage and Representative John Lewis’s opposition to the Defense of Marriage Act.

The ideas of grappling with racism as structural meant that each placed-based experience – whether face to face or virtual – reveals how institutions, such as schools, banks, and judicial systems, supported white supremacy. The Library’s digital collections, such as The African American Odyssey: A Quest for Full Citizenship and Protests Against Racism Web Archive, facilitate structural analysis of racism. Intentional use of primary sources assisted us in our commitment to achieve aims advanced by King’s (2020) Black Historical Consciousness principles and Jeffries’s (2020) framework for teaching race and racism.

The principles of Black Historical Consciousness (King, 2020) underscore the importance of teaching through, rather than about, Black history by centering experiential knowledge and perspectives of Black historical actors. Specifically, two principles – (a) Black agency, resistance, and perseverance and (b) Black joy – were used to foreground the humanity of Black people and guide the TPS CRF’s place-based learning experiences. Black agency, resistance, and perseverance highlight how Black people made decisions, acted in their own self-interest, and actively resisted oppressive structures. Amplifying the values of community and belonging, Black joy engages with Black people’s cultural and creative experiences. TPS CRF Consortium members embraced the pedagogical possibilities embedded in the principles of black historical consciousness’ acknowledgment of the humanity and complexity of Black people.

In his National Council for History Education (NCHE) address, Jeffries (2020) provides seven guidelines for educators when teaching race and racism: Be Clear, Be Positive, Be Open, Be Personal, Be Explicit, Be Intentional, and Be Proactive. Collectively, the guidelines push back against traditional narratives of the movement. The articles in this issue highlight: Be Open – Start where your students are, Be Personal – Share YOUR story, and Be Explicit – Personal vs. Structural. Collectively, these be (pun intended) useful for modeling how to teach about the institutional and structural issues people sought to address and redress with local, state, and national organizing. Literally starting, where students are, allows for learning more about the ways race and racism operate in their local and state contexts. Sharing individual experiences, while making connections to local and state public policies, provides an avenue to attend to structural racism. Place-based professional learning uses primary sources to illuminate the ways local communities organized in response to racist policies. This creates a compelling counter narrative to traditional approaches found in textbooks. Place-based experiences provide a counter, because students are able to understand how people in their communities were involved in the movement.

Combined with the TPS CRF’s place-based professional development approach, the frames offered by Jeffries (2020) and King (2020) were a guide for learning about the CRM in ways that (a) honor the roles of “ordinary people…capable of extraordinary acts” (Payne, 1995, p.5), (b) highlight the importance of state and local organizing, and (c) create curricular space for Black people’s humanity. Drawing on their learning, the Fellows submitted lesson plans after each placed-based study. The TPS CRF Consortium members reviewed all products and identified three themes – local matters, arts and agency, and radical joy – from the collective work. Prior to the Atlanta Professional Learning Conference, we assigned the Fellows to inter-state groups based on the themes. These groups co-created theme-focused albums using Library of Congress collections in the TPS Teachers Network: Arts and Agency Album, Local Matters Album, and Radical Joy Album. For example, the Arts and Agency Album explores the integral role of artistic expression in the long movement for civil rights.

Our How: Using Primary Sources to Teach the Civil Rights Movement

Fortunately, the tools and techniques needed to teach the civil rights movement accurately and effectively are at our disposal. (Jeffries, 2019, p. xiv)

The analysis of primary sources allows students to draw important conclusions, discover details about horrific events of the past, consider the origins of prejudice and stereotypes, and confront grim topics that feed contemporary fears (Potter, 2011). Understandably, educators are often preoccupied with which primary sources to use. Yet, capturing the range of justice issues in addition to the complexity of CRM actors requires an intentional focus on how primary sources are used with learners.

The ways in which professional development experiences are organized can illuminate how structural racism shapes personal experience. Taking up Jeffries’s (2020) Be Personal and Be Explicit approach, the TPS CRF Consortium members selected primary sources that countered traditional renderings of the CRM by centering the experiences of Black people. Furthermore, we connected personal racialized experiences and structural racialized impacts and outcomes. One way the TPS CRF Consortium members did this was, again, by centering Black voices and local or community stories. As a technique, primary sources from the local community coupled with Library of Congress digital collections invites students to examine (e)raced community stories in ways that capture the breadth and depth of racial and social injustices.

The articles in this issue detail how primary sources address the personal experiences of historical and contemporary actors in ways that address how inequities and white supremacy were maintained, but also, how Black people created spaces of joy and cultural expression in spite of them. In Beyond the Dominant Narratives of the Civil Rights Movement: Engaging with the Local Histories of the Black Community, Duke shares an example of how primary sources demonstrate African American community building. The lesson, which concerns the Bass Street community in Nashville, offers strategies that can be applied to other local communities. In Melodies of Resilience and Resistance: Exploring the African American Experience through Musical Analysis, Morton describes a lesson exploring the uses of music in the African American experience. Related to this, primary sources in the Library’s collections demonstrate how the theme of freedom found in spirituals resonates across African American experiences. Finally, Spiering and Cook share the impact of participation in the TPS CRF on educator teaching practices. Based on an analysis of the final session, the Fellows (a) were given access and time to engage with high quality resources, (b) increased their confidence in teaching the CRM accurately, and (c) were encouraged to create more meaningful and academically interesting lessons.

Conclusion

…[A] misunderstanding of the Black freedom movement—and therefore of the history of this country—had dire consequences for everyone, especially for all of us who believe that there is still the possibility of creating “a more perfect Union” in this land. As a result, one of the major challenges available to teachers in every possible institution is to introduce ourselves and our students to an alternative vision of the movement, to see it as a great gift for all Americans, as a central point of grounding for our own pro-democracy movement [emphasis ours]. (Harding, 1990, p. 29)

Professional development can create a community where we engage in difficult conversations over time that are connected to the democratic vision of the CRM. The type and nature of the primary sources we choose matter for accurately learning about the CRM. Teaching critically through primary sources means selecting a variety of sources to highlight how personal experiences contribute to understanding the structures (i.e., policies and practices) that enable or disrupt inequality. If students are to engage with primary sources deeply and in meaningful ways, we must begin by creating the context for educators to do the same. The TPS Civil Rights Fellowship is illustrative of the possibilities that exist when investments are made in teachers’ deep, sustained, and community-engaged learning.

References

Alridge, D. P. (2006). The limits of master narratives in history textbooks: An analysis of

representations of Martin Luther King, Jr. Teachers College Record, 108(4), 662–686. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9620.2006.00664.x

Anderson, C. B. (2013). The trouble with unifying narratives: African Americans and the civil rights movement in U.S. history content standards. The Journal of Social Studies Research, 37(2), 111–120. doi:10.1016/j.jssr.2013.03.004

Harding, V. (1990). Gifts of the Black Movement: Toward “A New Birth of Freedom”. Journal of Education, 172(2), 28–44.

Jeffries, H. K. (Ed.). (2019). Understanding and teaching the civil rights movement.

University of Wisconsin Press.

King, L. J. (2020). Black history is not American history: Toward a framework of Black historical consciousness. Social Education, 84(6), 335–341.

Lee, C. D., White, G., & Dong, D. (2021). Educating for civic reasoning and discourse:

Executive summary. National Academy of Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED611952.pdf

Oliver, S. T. (2016). Dealing with things as they are: Creating a classroom environment for teaching slavery and its lingering impact. In B. Jay & C. L. Lyerly (Eds.), Understanding and teaching American slavery (pp. 31–42). University of Wisconsin Press.

Payne, C. M. (2006). The view from the trenches. In S. Lawson & C. M. Payne (Eds.), Debating the civil rights movement, 1945-1968 (pp. 108–109). Rowman & Littlefield.

Potter, L. A. (2011). Teaching difficult topics with primary sources. Social Education, 75(6), 284- 290.

Vasquez Heilig, J., Brown, K., & Brown, A. (2012). The illusion of inclusion: A critical race theory textual analysis of race and standards. Harvard Educational Review, 82(3), 403-424. doi:10.17763/haer.82.3.84p8228670j24650

View, J. (2004). Introduction. In D. Menkart, A. D. Murray, & J. L. View (Eds.), Putting the

movement back into civil rights teaching (pp. 3–11). Teaching for Change.

![[Demonstrators marching in the street holding signs during the March on Washington, 1963] / MST.](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-ds-04000-04000v.webp)

![[African American men, women and children outside of church]](https://tpsconsortiumcreatedmaterials.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/service-pnp-cph-3c00000-3c03000-3c03300-3c03393v-e1708980496747.webp)